We’ve heard and read about MAGA almost daily since January. That said, “Making America Great Again” begs some key questions. None of them have simple answers. When exactly was America “great” and what made it so? And, according to the MAGA movement, when did it cease to be “great” and why?

There is an even more basic and underlying geopolitical question: what and where is America and who made it what it is? Nor is this as daft a pair of questions as might at first be thought and they are at the heart of Greg Grandin’s impressive new book, “America, América”.

Grandin is not afraid of addressing big questions and has crafted a scintillating re-casting of the origins and evolution of what was once called the “New World”.

Of course, there wasn’t anything “new” about it except in the eyes of those who sailed westwards in the sixteenth century and supposedly “discovered” it. The European conquerors and those who came after them found not an extension of the world they knew in their own continent but something different and deeply unsettling. Had God made more than one world and was this “new” one populated with people like them or something less than human? Did the laws and assumptions of the “old” world apply equally in the “new” or were the European conquerors literally outside and unbound by the laws applicable in Europe?

Grandin’s sweep and range is on a grand scale and he is invariably exhilarating to read. He has turned so much of the story we thought we knew upside down. Most fundamentally, he underscores repeatedly the hemispheric quality of America, a single continent from north to south. And from the sixteenth to the twentieth century, the story he tells is not about an Anglophone north and a Latin south but an interactive one across the whole continent from pole to pole.

Nor is his account one of an Anglophone vanguard in the north and a backward and reactionary Latin south. On the contrary, according to Grandin, it has more often than not been the south that has been less aggrandising, more progressive and more internationalist than the north.

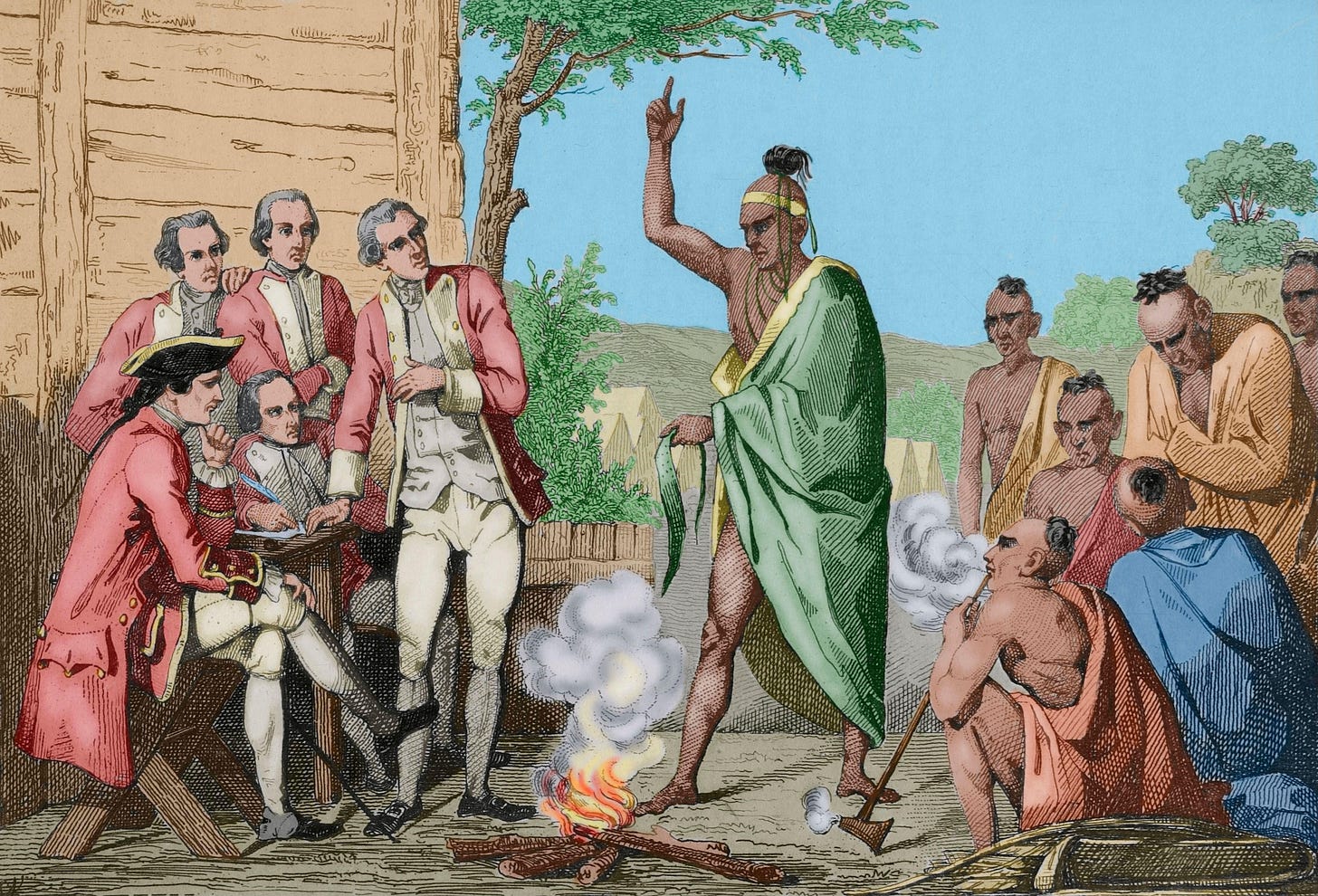

In terms of conquest, the Spanish came first and it suited Cortes and his fellow conquerors to view the lands they called América as new-found and the “natives” living there as fundamentally inferior. For new-found lands and their primitive inhabitants could be held to have no rights or entitlements and no land or property to call their own. Or so it was thought until a repentant (for he had started as an accomplice of the conquerors) and newly ordained member of the Dominican Order of friars, Bartolomé de las Casas, argued otherwise in the first half of the 16th century.

Las Casas insistently asserted that the Indians or native inhabitants he had met were reasoning people who shared in a common or universal humanity. With like-minded clerics influential with the Spanish Crown and with the Papacy over succeeding decades, Las Casa was instrumental in effecting an evolution in elite attitudes and acceptance of a common humanity. This shift did not however restrain the conquistadores.

With extreme and wanton cruelty, the conquerors suppressed the indigenous populations so as to grab the mineral and agricultural riches for their Spanish and Portuguese royal masters. And a fatal mixture of ruthless military attacks and imported diseases dramatically reduced local populations (by 80% in the island of Hispaniola, the modern day Democratic Republic and Haiti) and generated a demand on the part of the conquerors for replacement workers from Africa.

A pattern was set in the south which was replicated in the northern parts of the hemisphere. Though initially the Anglophone communities on the eastern seaboard showed more restraint, as the northern colonies secured independence they assumed a right to unlimited territorial expansion and transported slaves from Africa to work their lands. But in the Anglophone territories there was no early equivalent of Las Casas to recognise indigenous human rights.

As Grandin clarifyingly demonstrates, whilst patterns of territorial expansion and consolidation followed both in the north and south, it was most expansive in the north as the US pushed westwards and southwards in the course of the 19th century. Indeed, under the Monroe Doctrine of 1823, the US sought to exclude any further European colonisation in the Americas and thereby to establish for itself a degree of superintending oversight across the continent.

It was not the US but the new republics in the south which – informed by the arguments of the Venezuelan Simon Bolivar – sought pacific relations between sovereign states and in turn attempted to resist the overweening political and economic claims of their northern neighbour.

But, despite their best efforts even into the 20th century, the Latin republics could not arrest the erosion of the word “America” only to describe the hemisphere as a whole or halt its emergence as a synonym for the USA. After a long rearguard argument, the south Americans in practice grudgingly accepted “Latin America” as the commonly accepted description of the southern half of the continent.

All of that said, what Grandin shows is that, however it was described, the American hemisphere remained a single geopolitical entity. Furthermore, Latin America’s influence within and beyond the American hemisphere was considerable. Grandin claims persuasively that Latin American countries’ “progressive” economic and social goals helped shape the post-First World War political agenda across the continent and directly influenced Roosevelt’s “New Deal” in the 1930s.

More widely, he shows how from the late nineteenth century until the inter-war years and the emergence of the post-war international settlement, the Latin American states were notably influential in the evolution of the American continent and of that continent’s place in the wider world.

In Grandin’s telling, it was the Latin American states which engaged positively within a Monroe doctrine framework to sustain – notwithstanding US interventions in central America – recognition of their sovereign independence.

And he argues more widely still that it was Latin America which echoed Las Casas in its assertion of a universal humanity and which played an instrumental role in the origins of the international court in The Hague and later of the United Nations and of a rules-based international order.

However, in some of the most insistent chapters of his book, Grandin argues that the hemispheric relationship was increasingly unbalanced as a result of the US’s growing economic and political weight after the Second World War and was soured especially by the impact of a US-led narrative which viewed all international relations after 1947 as an ongoing ideological conflict between communism and capitalism.

To Grandin’s mind, it need not have been so if the more cooperative pre-war pattern set in the 1930s could have been maintained. The Latin Americans, more remote from the Cold-War interface, were more concerned to renovate their economies better to bear down on acute poverty in so many of their countries than to line up against the communist countries.

Renewed territorial and political engagement by a greatly empowered and assertive US in what it all too often saw as its southern “backyard” set a pattern which Grandin sees as having been destabilising and counter-productive. Post-war inflows of armaments as payment for large debts owed to the US especially, helped increase the institutional significance of the Latin American Armed Forces and the combination of that with continued economic and social distress helped open the way to numerous military dictatorships.

With a communist Cuba as a particular irritant and indicator of wider instability in the region, the US engaged in further military interventions across central America in the 1960s. Unity across the Americas became increasingly unattainable thereafter.

In the final section of “America, América”, Grandin reveals his contemporary viewpoint all too clearly:

“ [Woodrow] Wilson imagined a world without war. FDR imagined a world without fear or want. Today’s ..[US].. political class imagines nothing…..The international institutions and rules that Latin America helped create or inspire in the years after World War II, long enfeebled, are today nearly worthless.”

He adds:

“In the 1930s, the best of the Americas converged. Now, the worst, despite efforts by good people on both sides of the border to hold off the eclipse. If the Conquest inaugurated the ’slow creation of humanity’, we, America, América, seem to be living through its dismantlement”.

Grandin’s final chapter – as these quotations illustrate – is an angry end to his book.

At times, he might be thought too indulgent of América and too harsh on America; but either way his book as whole is a very serious and stimulating analysis of the historical evolution of post-Conquest America, all of America.

After finishing reading, it is impossible not to see that continent anew.

America, América: A New History of the New World by Greg Grandin, April 2025, Torva, £30