One of the wonders of J.R.R. Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings trilogy is its ability to completely engross the reader. The world Tolkien conjured up, though obviously fictional and fancifully so, is also unmistakably our world. And this was intentional. Tolkien hoped to create a mythology for his own England. His stories form a kind of literary protoevangelium, a mythical anticipation of the Christian world, that is to say, the real world.

And so Tolkien invented a mythical world, with its own languages, legends, peoples, and histories. Yet in the most fundamental sense, Tolkien did not create Middle-earth so much as he built it on real foundations. The moral stakes are the same as in our world. Virtues and vices are the same. Nobility and grace are the same. Goodness, both in the moral and metaphysical sense, is measured on a deeply human, and indeed Christian, scale. And so for all the hobbits and goblins and elves, his world retains a thoroughgoing realism.

This is why Tolkien could rightly describe his trilogy as a “fundamentally religious and Catholic work,” even though the stories themselves contain almost no direct references to religion of any sort.

In many ways, Tolkien’s triumph is singular. Yet it shares with all great literature an ability to convey profound truths. Great fiction always does this. Indeed, fiction often does this more effectively than non-fiction, which in its earnest endeavor to adhere to established, verifiable facts or its tendency to overestimate the reliability of human reason, can easily present a view of reality so narrow and partial that it obscures or distorts our grasp of the whole.

Surely this is one reason Christ spoke so often in stories and parables. He wrote no essays or treatises.

And of course, the enduring appeal of Tolkien’s stories is mostly due to their being compelling and interesting stories rather than the theory of myth which shaped their writing. (Though the latter may be a prerequisite to the former.) The epic scale of The Lord of the Rings – it is a very long story – allows a reader the time to become thoroughly engrossed.

Alas, all good stories must end (a fact which certain film studios seem loath to acknowledge). In recent years, the Tolkien estate has put out a slew of new additions to the Tolkien legendarium – previously unpublished bits of stories and partial histories. But The Lord of the Rings exists in the past perfect tense: a discrete, finite, and accomplished thing.

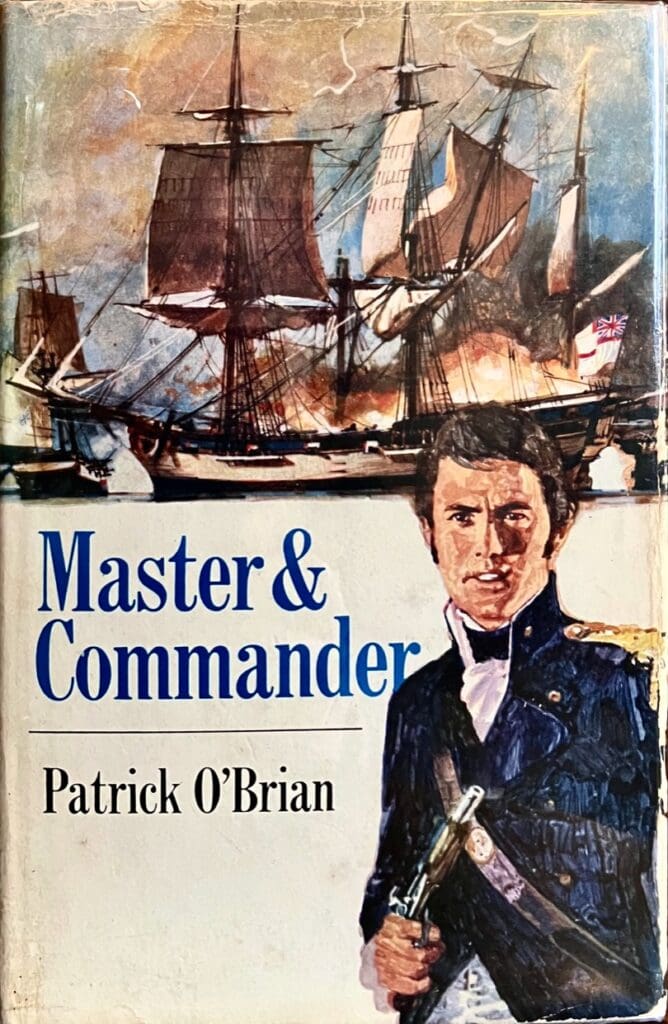

The English novelist Patrick O’Brian was no J.R.R. Tolkien. But in O’Brian’s series of historical novels – 20 in all, plus one unfinished – I have found, if not a rival to Tolkien’s beloved masterpiece, then at least a compliment. O’Brian portrays the careers of Captain Jack Aubrey of the Royal Navy and his friend Stephen Maturin, a physician, naturalist, and intelligence agent, through the Napoleonic Wars.

O’Brian invented no languages or mythologies. His novels are set amongst historical events, sometimes described with slavish accuracy. But in his characters –particularly Aubrey and Maturin – one discovers an astonishing breadth and depth of reflection on human nature.

I’ve been re-reading the novels in recent months, having aged a bit since I last read them. On this second reading, I’m much more attuned to a similar thing happening to Aubrey and Maturin.

The first novel opens with the protagonists as young men, Aubrey a newly promoted “Master and Commander,” and Maturin an impoverished, disaffected would-be revolutionary. Neither is married; both are at the beginnings of their careers (though with very different prospects before them.)

The friendship of Jack and Stephen – an unlikely pair, contrasting in physical appearance, temperament, religion (Stephen is a Catholic), and all interests save a love of music – allows for a fascinating study of human character, but perhaps more so, a study of the effects of time and fortune.

As their friendship deepens, each friend has time to notice and reflect on the sort of man his friend is becoming, and to wonder at the slow but seemingly inexorable changes in themselves. Years of physical hardship, danger, love, loss, sadness, and joy work upon the men.

And the reader has twenty volumes (about 15 years in the novels’ time) to grow intimately familiar with each character and to savor every detail of the slow work of time upon the human soul.

It is ultimately this moral realism – the surety that these characters inhabit our world, fictional though they may be and as flawed and sometimes disappointing as they are – that make O’Brian’s stories so engrossing, so true.

O’Brian was not a Catholic, though he lived for many decades in the south of France. His familiarity with Catholicism, and with the Mass especially, decidedly alters his understanding of time. Consider the following passage, in which Maturin attends Mass in Boston during the war of 1812:

There followed an interval on a completely different plane of being: with the familiar ancient words around him, always the same, in whatever country he had ever been (though now uttered in a broad Munster Latin), he lived free of time or geography, and he might have walked out, a boy, into the streets of Barcelona white in the sun, or into those of Dublin under the soft rain. He prayed, as he had prayed so long, for Diana, but even before the priest dismissed them, the changed nature of his inner words brought him back to the immediate present and to Boston, and if he had been a weeping man it would have brought tears coursing down his face.

So though O’Brian was not Catholic, through his characters, he presents a compellingly Catholic, indeed a liturgical, sense of reality. In his stories, the sea is always there, unchanging and ever changing, merciless, beautiful, glorious, and terrible as time. But O’Brian knew there was another plane, a higher plane, and when a vision of that breaks through into this unchanging and ever-changing world – this life at sea – it changes everything.