The Church is a poet, in the strict sense, since through the Spirit she makes poems, that is, beautiful, created objects. Her sacraments and liturgical year are poems: they have meaning and even tell a story. Likewise, each parish church is a poem, and each liturgy celebrated there. And every faithful Catholic must be zealous for this poetry.

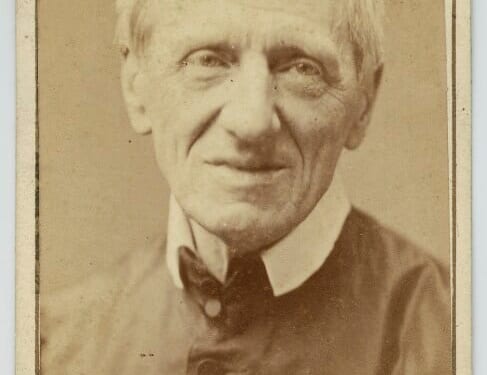

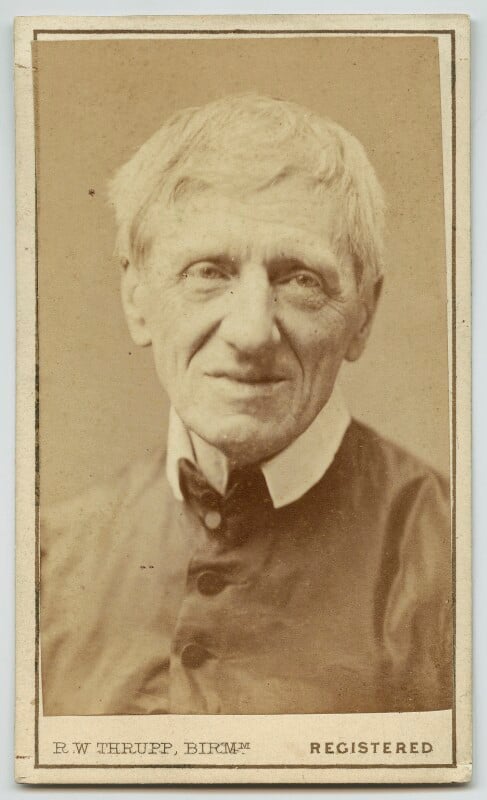

At least, so much I have gained by pondering Newman, Doctor of the Church. Newman traced the origin of his beloved Oxford Movement to a longing for this poetry. It was an attempt to recover the poetry that properly belongs to the Catholic Church.

It began in 1827, with the publication of John Keble’s book of poems, The Christian Year. Few know this book today. Evidently, it played its role and departed. Yet historians say that, with perhaps 1 million copies sold, Keble’s was the most popular volume of English verse in the 19th century.

The Christian Year contains a poem for each Sunday in the liturgical year, and for various feasts, such as St. Stephen’s and Holy Innocents. Christian families used it as a breviary, reading aloud the poem for the week and memorizing it together. In doing so they would also pray, because, as Keble says in his Dedication, his poetry was the fruit of prayer:

When in my silent solitary walk,

I sought a strain not all unworthy Thee,

My heart, still ringing with wild worldly talk,

Gave forth no note of holier minstrelsy.

Prayer is the secret, to myself I said,

Strong supplication must call down the charm,

And thus with untuned heart I feebly prayed,

Knocking at Heaven’s gate with earth-palsied arm.

Fountain of Harmony!

Keble, then, would re-enchant the world by enchanting it, by calling down “the charm” in prayer.

Newman’s assessment:

[Keble] did that for the Church of England which none but a poet could do; he made it poetical. . . .the author of the Christian Year found the Anglican system all but destitute of this divine element, which is an essential property of Catholicism; a ritual dashed upon the ground, trodden on, and broken piece-meal; prayers, clipped, pieced, torn, shuffled about at pleasure, until the meaning of the composition perished, and offices which had been poetry were no longer even good prose; antiphons, hymns, benedictions, invocations, shovelled away; Scripture lessons turned into chapters. . .a smell of dust and damp, not of incense. . .the royal arms for the crucifix; huge ugly boxes of wood, sacred to preachers, frowning on the congregation in the place of the mysterious altar. . .and for orthodoxy, a frigid, inelastic, inconsistent, dull, helpless dogmatic, which could give no just account of itself.

His happy magic made the Anglican Church seem what Catholicism was and is.

Because of the success of The Christian Year, in 1831 Keble was appointed Chair of Poetry at Oxford. Two years later, on July 14th, he preached his famous sermon on “National Apostasy,” which Newman in his Apologia later said “I have ever considered and kept. . .as the start of the religious movement of 1833.”

Thus, the Oxford Movement and therefore Newman’s own conversion began with poetry. From out of the shadows of poetry (ex umbris et imaginibus), Newman entered into the truth poetry (in veritatem) of the Church.

For Newman, Keble was part of a broader movement of yearning after beauty and truth which today we call the “Romantic Movement” (on which see the perceptive commentary of Andrew Klavan, The Truth and Beauty). But whereas the Romantic poets, whom Keble admired, looked to build a new civilization on the ruins of a dead rationalism, Keble, rather, aimed to revive something old, which had preceded the Enlightenment.

Such a project never had been necessary in the Catholic Church, Newman comments: “Poetry is the refuge of those who have not the Catholic Church to flee to, and repose upon; for the Church herself is the most sacred and august of poets,” which is why poetry is “more commonly found external to the Church than among her children.”

About the Romantic Movement itself, Newman says, “there has been for some years, from whatever cause, a growing tendency towards the character of mind and feeling of which Catholic doctrines are the just expression.” Wordsworth and Southey were important here and especially Coleridge:

a very original thinker, who. . .advocated conclusions which were often heathen rather than Christian, yet after all instilled a higher philosophy into inquiring minds, than they had hitherto been accustomed to accept. In this way he made trial of his age, and found it respond to him, and succeeded in interesting its genius in the cause of Catholic truth.

Yet Newman gives the palm to Sir Walter Scott:

A great poet. . .raised up in the North, who, whatever were his defects, has contributed by his works, in prose and verse, to prepare men for some closer and more practical approximation to Catholic truth. The general need of something deeper and more attractive than what had offered itself elsewhere, may be considered to have led to his popularity; and by means of his popularity he re-acted on his readers, stimulating their mental thirst, feeding their hopes, setting before them visions, which, when once seen, are not easily forgotten.

So then, how today should we heed these teachings of Doctor Newman?

Obviously, by continuing to foster in young persons a love of the tales of Tolkien and C.S. Lewis, as these works play the role today which Scott’s novels played then.

And yet also by being zealous for the poetry of the Church. How absurd it would be, if someone led forward by the “hopes and visions” of this literature, should find in any Catholic church “a ritual dashed upon the ground, trodden on, and broken piece-meal. . .hymns, benedictions, invocations, shovelled away. . .a smell of dust and damp, not of incense. . .and huge ugly boxes of wood. . .frowning on the congregation in the place of the mysterious altar”!