The word “nostalgia” was coined in the seventeenth century by a Swiss physician named Johannes Hofer. The word was a Latinized combination of two Greek words: nostos, meaning “a return home” (think Odysseus), and algos, meaning “pain.” Hofer used his new word to describe a medical condition, one he noticed to be particularly common among Swiss mercenaries serving abroad, which might best be described as acute homesickness – homesickness so acute that it could sometimes be fatal.

The word remained in use as a medical term, often applied to soldiers, well into the nineteenth century. For example, in 1865, an American newspaper described conditions at a major prisoner of war camp where captured Confederate soldiers were housed:

At Camp Douglas, Chicago, there are fourteen hundred prisoners on the sick list, with an average number of interments of six per day. One of the most frequent causes of death is nostalgia, which is the medical designation for home sickness.

It wasn’t until the early twentieth century that the word nostalgia took on its present meaning: a fond remembrance of the way things used to be, tinged with sadness that things are no longer so.

No one would argue that missing home is a uniquely modern phenomenon. Nor is the fond remembrance of the good ol’ days something new. But there is something about the dislocation of the modern era – both physical dislocation and the dislocation caused by the rapid, if not accelerating, pace of cultural and social change – that gives both meanings a particular relevance for the contemporary world.

Surely this modern sense of dislocation has contributed to nostalgia becoming such a defining part of contemporary American life. It shapes our politics, saturates our popular culture, and even shapes how we think of the future.

And there is no time of year in which the American appetite for bittersweet indulgence in nostalgia is more on display than during Advent.

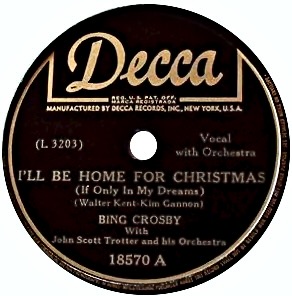

Bing Crosby first recorded “I’ll Be Home for Christmas” in 1943, when millions of American men were overseas fighting in Europe and the Pacific. “It’s a Wonderful Life,” one of the greatest movies – not just Christmas movies – of all time, came out in 1946. “A Miracle on 34th Street” came out a year later. “It’s Beginning to Look a Lot Like Christmas” was recorded by both Perry Como and Bing Crosby in 1951. Como’s “(There’s No Place Like) Home for the Holidays” has been a staple on the radio since 1954. That same year, “White Christmas” came out (though the eponymous tune had been written in 1942).

Now, one may object that I am connecting nostalgia and Advent, but all these songs and movies are “Christmas movies” or “Christmas songs.” Sure, we call them that, but they’re really all about Advent – about the sense of longing which steadily grows as we approach Christmas. (Besides, you can call them “Christmas songs” all you want, but if they start playing just after Thanksgiving and stop playing right after Christmas, they’re “Advent songs.”)

Notice, too, that each of the songs and films I listed came out within a decade of the Second World War – the greatest collective experience of homesickness and (for the lucky ones) safe return in American history. Many of these make explicit reference to the war. And while thousands of songs and films about Christmas (and Advent) have been made since, and while some have even become immensely popular, the post-War, pop-culture, nostalgia factory which produced the old hits remains the standard against which the more recent additions are measured.

One may also object that lots of “Christmas movies” and “Christmas songs” are schlock, which I’ll grant. But that only underscores the point that the actual artistic merits matter less than the fact that we associate these films and songs with the approach of Christmas. We want to feel like we’re going home for Christmas, like returning to the places we knew and the way things were when we were young, or at least to indulge a little of the pain and sadness of no longer being able to do so.

In this sense, “Home Alone” (which I have never cared for) is as perfectly a Christmas movie for Gen-X as “Elf” is for Millennials, or “Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer” is for Baby Boomers. They are all about dislocation and homecoming in the days leading up to Christmas. And the feeling of nostalgia they evoke, especially if we first saw them long ago as children, only grows with repetition. Watching these films becomes an Advent tradition, capable of evoking nostalgia in its own right.

There is good reason that all the days and weeks before Christmas are so laden with nostalgia. Beneath the busy-ness and noise of the season, beneath the glitz and materialism, and beneath the nostalgia and traditions (both sacred and profane), beneath all the schlock and sentimentality is the underlying human longing for home, for a place we know and where we are known, a place where we are secure. And for all the ridiculous or misguided ways we sometimes seek to satisfy that longing, the longing itself is a gift, a reminder of that for which we were made.

We Christians know that Advent is a season to prepare for the arrival of the Christ child. In his coming, all God’s promises to his people will be fulfilled. The God from whom we were separated in the Fall will come among us, and the deepest longing and restlessness will give way before the Prince of Peace. He makes a home among his people so that we may find a home in him.

Homesickness is the human condition. In Advent, we recall the remedy: Verbum caro factum est et habitavit in nobis.