In his excellent recent book, Strange New World, Carl Trueman cautions Christians against naïve optimism in our “chaotic, uncharted, and dark era.” It’s a judicious point. There is plenty in today’s culture to shock anyone into sobriety, religious believers most of all. At the same time, there’s a case to be made for “informed optimism,” or rational grounds for believing that Christianity will receive a more serious hearing in the West in years to come.

For over sixty years, after all, we have lived under the tyranny of a collective declaration that I am my own, and no one else’s – that I decide matters of life, and the giving, taking, or preventing of life; that I, and no one else, have the right to do with my body whatever I see fit.

And this repudiation of the truth that we are not our own can now be judged by its fruits, which are everywhere around us. The declaration that I am my own, the fundamental battle cry of the sexual revolution, has rendered life radically different, and in several respects, worse for us than for any other human beings in history.

That is a large claim. The record bears it out.

Living by the credo I am my own, and no one else’s has created massive suffering unnoticed until recently by anyone but the believers. That ingrained denial is now changing – and it is changing precisely because the damage out there has become unavoidable.

The toll of the idol of autonomy can be found all over: in today’s legions of unhinged young people, in rates of psychological problems that have been rising for decades, in academic studies of loneliness, in social unrest, in the increasingly expressed wistfulness of a world missing its children. The verdict is in.

Further, the declaration that I am my own when it comes to sex and sexual pleasure has resulted in the single biggest impediment to romance and family and marriage today: the compulsive consumption of pornography by large numbers of young men, and some young women.

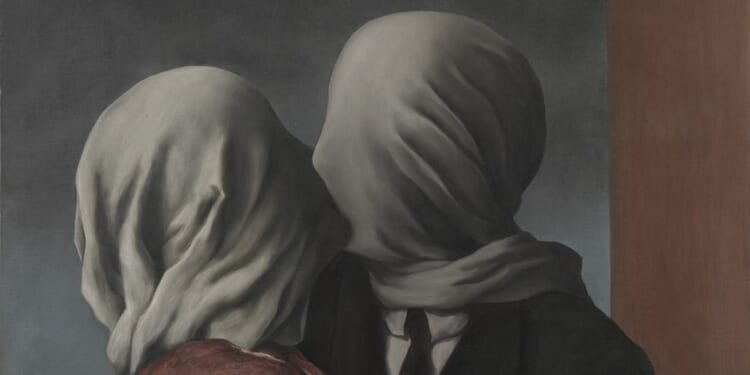

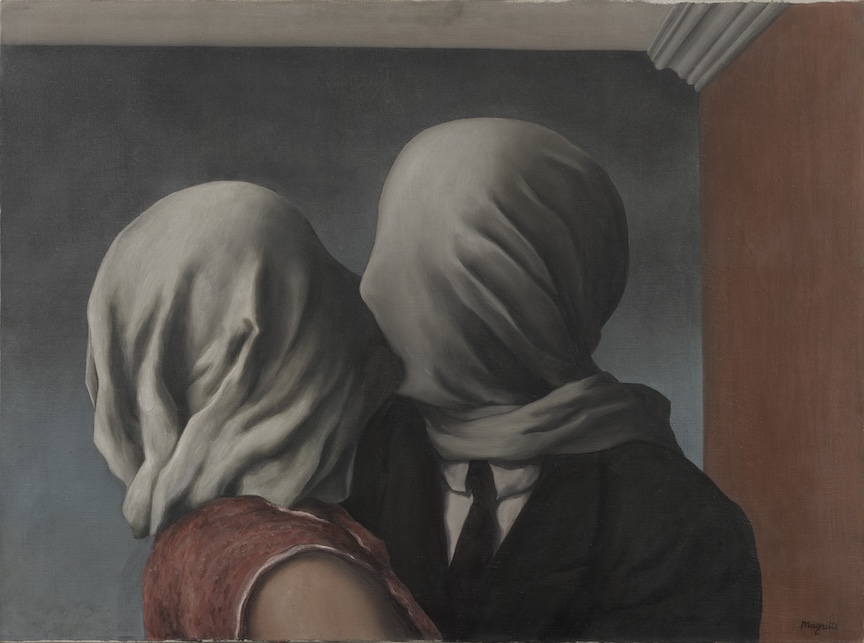

As therapists know, one result of that obsession is individuals rendered incapable of real-time romance. This terrible outcome, which may be the most terrible of all the revolution’s outcomes, turns that declaration I am my own, and no one else’s, into an epitaph for love itself.

This brings us, paradoxically, to a first ground for hope. So patent and inarguable is the damage out there that voices outside religious orbits have finally started calling attention to it.

New skepticism, and new indictments of unbridled sexual autonomy, are now issuing – including from writers who say they would rather not align themselves with traditional Christian teaching, but that logic and evidence led them to the same vicinity, nonetheless.

This turn toward revisionism, too, is all to the good. To have secular voices align with Church teaching on social issues, however reluctantly, and regardless of whether they credit Christians or Christianity at all, is a clear win for the Cause.

This points us to one more source of hope. In another turn that would not have been predicted even ten years ago, religious conversion and observance are no longer unheard of, even on the most elite and secularized campuses. In fact, they are on the increase – as liberal intellectual Mark Lilla noted last year (and uneasily) in an essay for the New York Review of Books about his own campus, Columbia University.

“In the past decade,” he observed, “interest in Catholic ideas and practice has been growing among right-leaning intellectual elites, and it is not unusual to meet young conservatives at Ivy League institutions who have converted or renewed their faith since coming to college.”

Columbia is not alone. Last spring, I gave talks at my own alma mater, Cornell University, long the most secular of the Ivies, whose political culture is perennially steeped in the hard left. Impressive signs of religious life have emerged there: in COLLIS, a Catholic intellectual institute and speaking program with energetic, committed leadership; in Chesterton House, a Protestant residence and hub, whose programming includes Bible study, good works, communal prayer, and other fellowship; and in a contagious esprit du corps across campus between Protestants and Catholics.

Elsewhere, on other quads, initiatives and institutions are proliferating, delivering anew traditions of the faith. Thomistic Circles, which shares the teachings of St. Thomas and others, draws curious students from all over.

At University of St. Thomas, Houston, to name another, exciting new Catholic programming is underway, especially at the Nesti Center for Faith & Culture; it includes the only Master of Arts offered in the world in Catholic Women and Gender Studies. A recent, robustly attended two-day winter symposium on what John Paul the Great called “feminine genius” offered one more measure of this avid Catholic community at work.

To reflect on such unexpected stirrings is to realize something easy to miss in this age rightly described as “chaotic, uncharted, and dark.” We have not returned from the experiment of the last sixty years empty-handed, after all.

In a way that is not widely understood, but will be, today’s postrevolutionary disorder tells us something. It tells us that living as if we are not our own protects us better than living under expressive individualism. The truth of Christian teaching is visible in the negative record of living without it.

Someday, more souls to come will understand – and reject – today’s autonomy-first credo. When that happens, Christians of the future, and others, will look backward for the signs leading to that future awakening. And they will find that as of early 2026, an unanticipated, significant number of them are flashing right here and now.

The post ‘You Are Not Your Own’ appeared first on The Catholic Thing.