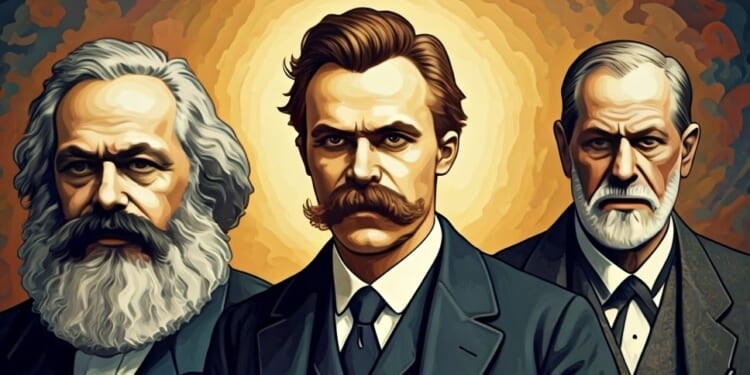

What we call Western civilization is in a precarious state today, challenged by the loss of religious values, a threat from aroused Islamic radicalism, romantic notions of “collectivism,” and a dangerous decline in the value of freedom of speech and thought. Paul Johnson, a non-academic historian and an example of the amateur being superior to the professional, in his study of the West from World War I to the 1980s, Modern Times, traced the roots of this crisis to the malign influences of certain key European figures: Nietzsche, Darwin, Marx, and Freud, each of whom undermined Europe’s confidence in its beliefs and traditions. He argued that Nietzsche’s “death of God” and rejection of the religious impulse created the vacuum that would be filled with the 20th century’s “new messiahs”: Lenin, Hitler, Stalin, and Mao. Although published originally in 1983 and revised in 2001, I think there is still much we can learn from Modern Times in these our own harrowing times.

Johnson’s history begins, unlike most studies of the 20th century, not with political developments leading up to the outbreak of World War I but with the impact of the thought of highly influential cultural figures. In 20 long and detailed chapters, he traces the key events that brought the West to a near collapse and then to a rallying led by Pope John Paul II, President Ronald Reagan, and Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher, among others, who are the heroes of the century in his view.

For Johnson, World War I was a catastrophe that destroyed European progress and eventually led to the world of totalitarianism that cursed the next three decades. He rejects the idea of historical inevitability. The war and its aftermath were a choice that ended with European civilization left in the hands of inferior or weak leaders. Among those he singles out for leaving the West in a parlous state are Tsar Nicholas II, whose weakness and indecision led Russia to war; General Ludendorff, the architect of total war and Johnson’s personal bête noire; and President Woodrow Wilson. Wilson’s vaunted concept of national self-determination, Johnson argues, opened the door in Europe to nationalist strife and helped lay the ground for those “terrible simplifiers” Lenin, Mussolini, and Hitler.

Only the United States emerged from the war in a more powerful position than when it began. In the chapter “The Last Arcadia,” Johnson has high praise for the American record of the 1920s, foreshadowing a trend that has developed among historians in recent years. He praises Calvin Coolidge for his handling of the economy, which reached a level of prosperity during his presidency than in any past society, one that would not be matched until the 1950s under another figure Johnson admires, President Eisenhower. The economic crisis of the 1930s, Johnson believes, was mishandled by President Franklin Roosevelt, whom he treats as a dilettante and gives little credit for ending the Great Depression, which he believes, along with most historians today, ended only with the outbreak of war.

Johnson argues that even American culture surpassed Europe’s in the 1920s, with writers like Ernest Hemingway, Sinclair Lewis, and F. Scott Fitzgerald taking American literature to new highs. At the same time, he notes how they, like their European counterparts, were duped by the myth of a new Soviet democracy. He has high praise for George Orwell, however, who demolished the idea of Communism as a form of democracy in his exposé of Russian treachery during the Spanish Civil War and such later famous works as Animal Farm and Nineteen Eighty-Four.

Johnson takes a harsh view of the behavior of Great Britain after WWI, arguing that its political leadership was at a loss for how to deal with the nation’s economic crisis. In one of the bon mots sprinkled throughout the text, he notes that once the British Empire became truly worldwide, the sun never set on its problems: political, economic, and imperial. He correctly credits Winston Churchill, another of his heroes, for saving his nation, and the West, from defeat in the early years of World War II.

Johnson’s sketches of Churchill and other dominant figures of the 20th century are a definite strength of the book. Mussolini, for example, was a mixture of romance and drama who was corrupted by power and the weakness of a semi-industrialized Italy that he sought to turn singlehandedly into a great power. Lenin was pure evil, a 20th-century ideologue consumed by hatred and convinced that only his interpretation of Marxism was correct. He left Russia in ruins and passed it into the hands of an even more brutal leader, Stalin.

Equally insightful is the connection Johnson draws between Hitler and Lenin, both believers in social engineering no matter the cost in human life. Hitler is described as a “race socialist” who saw the dynamic of history revolving not around economic classes but races. In an observation that reverberates today, Johnson notes that among the most enthusiastic anti-Semites in Germany were university students and that Hitler was popular with primary and secondary school teachers as well as with university professors.

In his chapter on Germany, Johnson argues that the German people were duped by their military leaders into entering World War I. He regards Emperor Wilhelm II as an exemplar of how personal weakness can become treachery. The German General Staff lost the war but moderates in Weimar who inherited a defeated Germany were seen as nevertheless responsible for the nation’s humiliation, dooming the concept of republican government. He makes an interesting point that the bitter anti-Semitism of the Weimar era was “a derivative of Marx’s hatred of the bourgeoisie,” which became personified by “the Jews.”

Johnson’s chapters on World War II contain some interesting insights on why the Allies won. He labels Hitler’s two greatest blunders as the decision to attack the Soviet Union before he had eliminated the threat from Great Britain, which was backed economically by the United States, and his gratuitous decision to declare war on the United States four days after Pearl Harbor, an act not required by his alliance with Japan. He believes, incorrectly in my view, that President Roosevelt would not have been able to persuade Congress to make war on Germany had not Hitler made this blunder. Yet America was all but at war with Germany by the autumn of 1941.

Johnson regards FDR as a poor wartime leader and accuses him of “illusions and frivolity” for believing that China was a great power and that he could trust Stalin. The latter misjudgment cost the United States and Europe dearly in the aftermath of the war and laid the groundwork for the Cold War. In dealing with traditional military history, however, Johnson seems unsure of himself at times. For example, he relies on some shaky sources for some of his statistics, such as the discredited Holocaust-denier David Irving, who claimed that the bombing of Dresden in February 1945 caused 230,000 deaths. The best estimated figures, 25,000–35,000, are bad enough. He does make a strong case, however, that Japan would not have surrendered without the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, citing the refusal to surrender during the bloody battles of Iwo Jima and Okinawa as examples of Japan’s fanaticism.

The last third of Modern Times covers the period from the end of the Second World War to the 1980s. It is more commentary—very high-level commentary—than history. His chapter on China under Mao, whom he compares for sheer brutality to Stalin, is worth the price of the book alone. In dealing with Stalin and Mao, Johnson takes special aim at the experts, usually intellectuals, who almost unfailingly got everything wrong. Author Jan Myrdal, for example, ranked Mao just behind Marx and Lenin for solving the problem of how the idea of “revolution can be prevented from degenerating.” Business types were not far behind in misreading the times. David Rockefeller praised Mao’s China for its “national harmony … while fostering high morale and community of purpose.” Estimates of the number who died during Mao’s rule, especially the Great Leap Forward, range from 35 to 80 million—or roughly the population of the modern U.K.

The chapters on the Third World contain some of Johnson’s shrewdest insights. A particular favorite of mine, “The Bandung Generation,” discusses the difficulties Third World nations faced at the time, especially in Africa, as they attempted to modernize. Despite predictions of many scholars like Arnold Toynbee—what Johnson labels “the new humbug”—that Asia and Africa would escape the travails that plagued the modernization of the West, the Third World in the 20th century experienced four decades of war, racial violence, and economic catastrophe. A section dealing with the fate of the South African republic makes particularly sad reading. Without excusing the practice of apartheid, it is nevertheless a fact that it was once the most prosperous nation in Africa because of its rich stores of gold, iron ore, and coal. It is now an international disaster and features one of the most brutal regimes in Africa.

A major theme of Modern Times is Johnson’s conviction, as a Catholic and a conservative, that the intellectuals and what he calls “the system builders” (what we in 2026 would call “the elites”) were responsible for much of the evils of the 20th century. He would go on to write Intellectuals, excoriating their record of misjudgments and disastrous prescriptions and policies.

Modern Times, despite some flaws, remains the best single overview of the 20th century in print. Fifty double-column pages of notes attests to the scope of Johnson’s research. In fact, it is difficult to imagine anyone today who could undertake such a task. Modern Times will remain the standard interpretation of the century when the West nearly committed suicide. The question before us now is, have we learned anything, given how so much of the West seems determined to make the same suicidal mistakes?