Pope Leo has been traveling in Turkey and Lebanon, doing what popes do on such occasions: Visiting religious and political leaders, signing agreements about further “dialogue,” calling for peace and respect for human dignity. All good things, and this pope does them with notable dignity. But they’re not the main thing. And without the main thing, other things have quite limited prospects. The main thing, the reason for the trip in the first place, was and is the truth confirmed at the Council of Nicaea (Iznik, Turkey today) in 325 A.D. that Jesus was not only a great man – as even many secular people today concede – but that He is the eternal Son of God and the Savior of the world.

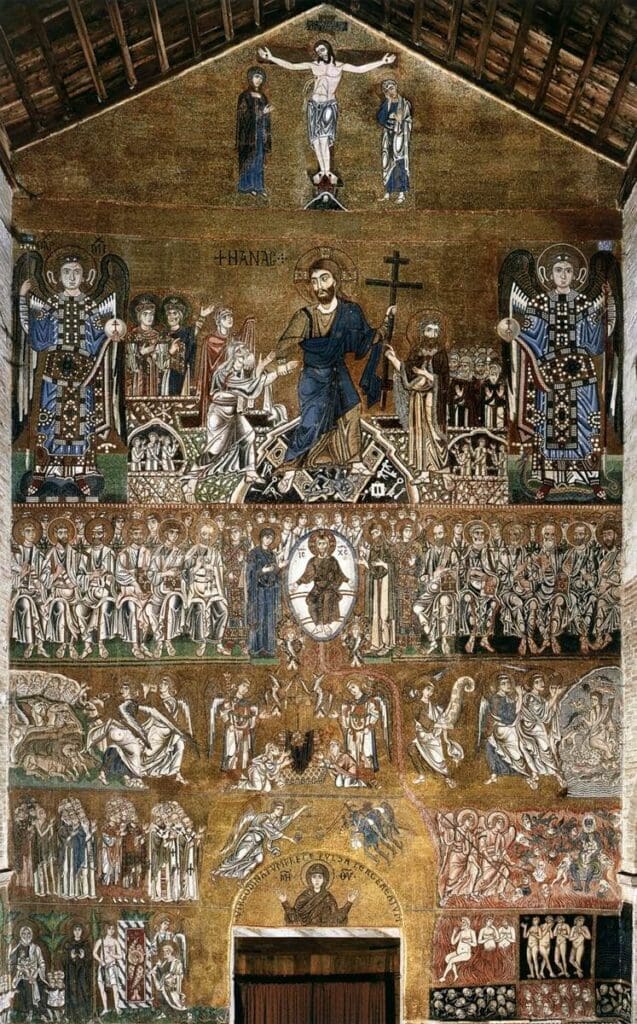

Indeed, though Leo has spoken vaguely of some theological controversies as no longer relevant, he also made a point of warning in Turkey that among our many postmodern problems, “there is also another challenge, which we might call a ‘new Arianism,’ present in today’s culture and sometimes even among believers. This occurs when Jesus is admired on a merely human level, perhaps even with religious respect, yet not truly regarded as the living and true God among us.” Arianism may seem to be one of those obscure theological controversies that no one much cares about anymore. But at Nicaea, exactly 1700 years ago, it was a hot topic because Arianism was widespread. And continued to be for centuries. And now, again.

This is all well-known to anyone who has looked into early Church history. But many people don’t realize how widespread Arianism actually was. When the Vandals invaded North Africa, around the time of St. Augustine’s death (430 A.D.), they came not only as “barbarians,” but Arian “Christians.” The Roman Empire itself “fell” in 476 A.D. when Odoacer, a Gothic “barbarian,” deposed the last Western emperor. The causes of Rome’s fall are much debated, but it was not by pagan incursion: Odoacer was an officer trained in the Roman Army with connections to the Eastern Roman emperors – and though tolerant of Catholics, an Arian.

Arianism appealed to soldiers, who saw Jesus as not only holy but, in his bravery during torture and death, heroic. It’s an odd view for many now. For centuries, the West has tended to turn Jesus into a “nice” figure, all warm and fuzzy. But maybe those soldiers saw something in Him that we might benefit from, especially as Christians are being persecuted around the globe.

Leo’s emphasis on Jesus as “the living God among us” also ties in with his warnings about another heresy. As an Augustinian, he’s quite sensitive to contemporary “Pelagianism,” which the great bishop of Hippo famously combatted about a century after Nicaea. Pelagius was a Celtic-British theologian who was thought to believe – recent scholars, of course, clash about this – that we are capable of following the precepts of the law, without the need for divine grace.

I’ve seen Pelagius described in some popular accounts as quite reasonable. There are rules. We are rational beings. We can follow them. Which of course ignores our daily experience, to say nothing of St. Paul: “the law is good. . . .but I see in my members another principle at war with the law of my mind, taking me captive to the law of sin that dwells in my members.” (Romans 17:16 & 23) Augustine, the Doctor of Grace, went after Pelagianism hammer and tongs, and left a great legacy of understanding how dependent we are on God – not our own will.

Pope Leo has recalled this main current in the tradition as well:

the greatest mistake we can make as Christians is, in the words of Saint Augustine, “to claim that Christ’s grace consists in his example and not in the gift of his person” (Contra Iulianum opus imperfectum, II, 146). How often, even in the not-too-distant past, have we forgotten this truth and presented Christian life mostly as a set of rules to be kept, replacing the marvelous experience of encountering Jesus – God who gives himself to us – with a moralistic, burdensome and unappealing religion that, in some ways, is impossible to live in concrete daily life.

This classic Augustinian view should not be understood as denying moral rules. Rather, it puts grace and the love of God first, which are the deep realities that make it possible for us to live the Christian life. Pope Benedict put it trenchantly: “Being Christian is not the result of an ethical choice or a lofty idea, but the encounter with an event, a person, which gives life a new horizon and a decisive direction.”

One notable thing about Pope Leo’s pilgrimage is his decision not to pray in Istanbul’s Blue Mosque, something which Popes Benedict and Francis both did. He took off his shoes, visited “as a tourist,” but maintained a bit of distance from Islam. And rightly so. Alongside the neo-Arianism that denies Christ’s divinity, and the neo-Pelagianism that implies that we can save ourselves, a false universalism and indifferentism – “God wills a multiplicity of religions” as Pope Francis said in a careless moment – has arisen in the modern world, even in the Church.

Pope Leo’s seeming resistance to that in the Blue Mosque is a small gesture, to be sure. But it’s worth noting, nonetheless, because it’s in such small details rather than the usual worldly “issues” that interest the mainstream media that we glimpse the necessarily countercultural nature of the Faith today.

Indeed, we need more of that. It’s a delicate thing to believe in the radical importance of the Faith on the one hand, and on the other, in public, to talk as if peace and brotherhood result from dialogue rather than the only true source of charity: Jesus Christ. Leo, like his predecessors, often talks the usual public talk. But it would be good if, at this point in history, he were also to become even more openly Augustinian, precisely about the difference Christ makes even for public things.