There’s another basilica called St. Peter’s in Rome, located near the Colosseum. San Pietro in Vincoli (“St. Peter in Chains”) is a minor basilica that gets its own share of visitors, many of whom come for just one reason.

Therein lies the “tomb” of Julius II, although the late pope is not interred there. Julius (Giuliano della Rovere) now lies in the other St. Peter’s, the world’s greatest church, next to his uncle, Pope Sixtus IV.

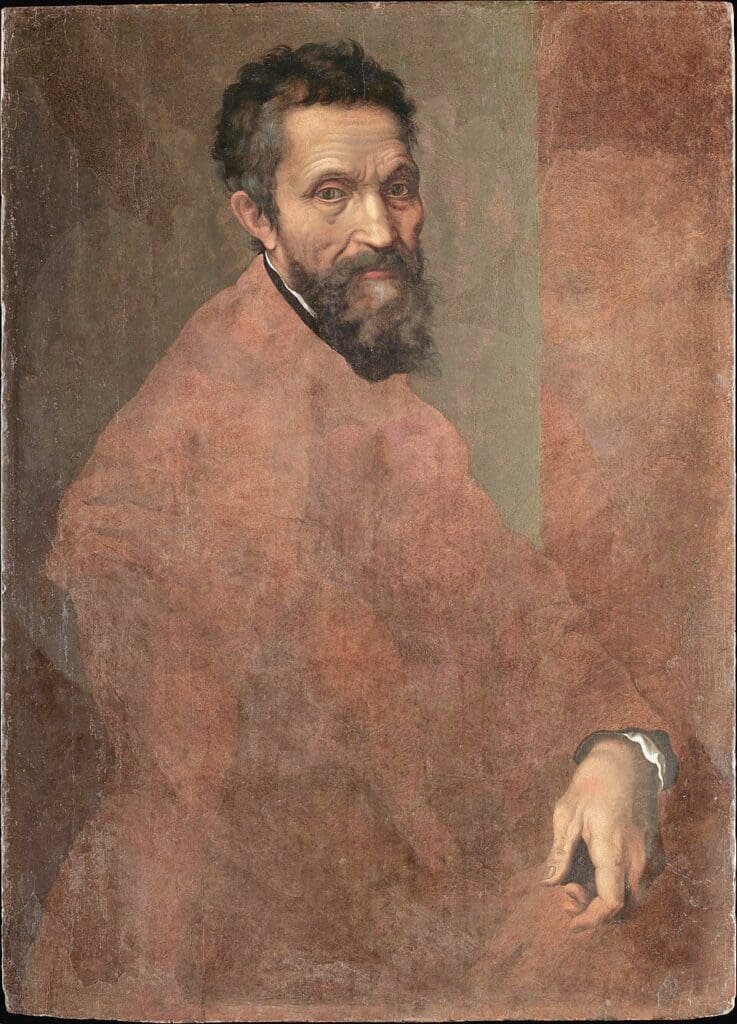

Julius, who had no small opinion of his august self, wanted a grand memorial to his life and papacy, so he brought Michelangelo Buonarroti to Rome to design it. The great, 30-year-old artist accepted with gusto, visualizing it as his life’s great work. And it’s to see this (especially its central sculpture) that people come to San Pietro in Vincoli.

What they see, however, is a work very much diminished from the original vision of Julius and Michelangelo because problems arose.

Julius decided that, having Michelangelo in his employ, the artist was just the man to illuminate the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel. Michelangelo had begun to work on the tomb in 1505 but was forced to put the project on hold in 1508 to climb the scaffolding in the Chapel and begin painting what many consider the greatest achievement of the Renaissance (if not in the whole history of art), a project he worked on for four years, completing the ceiling on October 31, 1512.

Julius was relieved. Now, he assumed, he’d live to see the tomb that would be a monument to his monumental life. Michelangelo’s original plan was for an enormous, free-standing, three-tiered sort of wedding-cake structure featuring 40 statues. It would be 23 feet wide, 26-1/4 feet tall, and 36 feet deep, and fairly dominate the interior of the new and equally enormous St. Peter’s at the Vatican, then under construction. And it might have worked if sited there, but it was not to be. Because it was at this point that the project came to a halt.

Why is not entirely clear. To be sure, the construction of the new St. Peter’s was a drain on the Vatican treasury, and its then-chief architect, Donato Bramante, was no friend of Michelangelo, and he may have convinced Julius that overseeing the construction of one’s own tomb was bad form for a holy man.

And there were wars, of course – with Julius leading the army of the Papal States. And, on the gloomy horizon, religious dissent that would lead to the Protestant Reformation.

The Vatican balance sheet was sliding into the red.

But Julius would not abandon the tomb project. In fact, he issued a bull (February 19, 1513) declaring that Michelangelo would be the only one to craft his tomb – a very high-powered back-to-work order. Michelangelo had finished his work on the Sistine Chapel a few months before. So now, Julius must have thought: Now he can finish my tomb!

Two days later, the pope died.

Michelangelo did finish the “tomb” in 1545, just two years before Pope Paul III would name him Chief Architect of St. Peter’s.

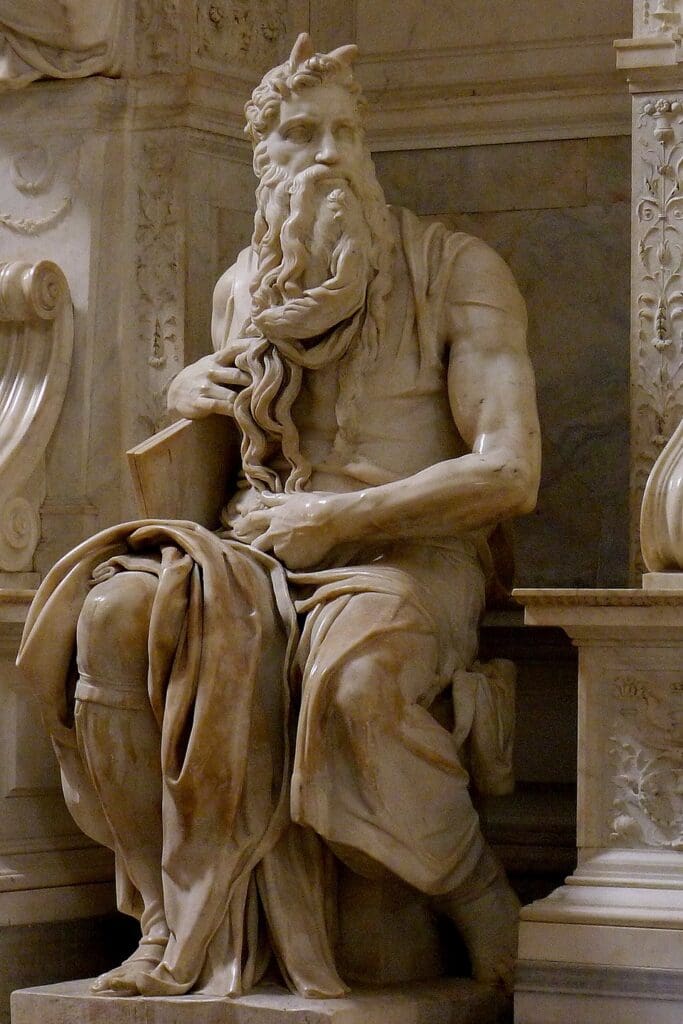

In the scaled-down tomb-that-is-not-a-tomb at St. Peter in Chains, Julius is not the centerpiece; Moses is. It’s Moses that people have flocked to see for more than four centuries. The church is beautiful, and the tomb is interesting, but it’s Michelangelo’s astonishing sculpture of Moses that amazes.

Among the unlikeliest of its admirers was Sigmund Freud. “Every day,” Freud wrote, “for three lonely weeks of September 1913, I stood in the church in front of the statue, studying it, measuring it and drawing it.”

He asserts that his interest in art is the “subject matter” rather than in “formal and technical qualities,” which he insists are what concern the artist. That, I think, is not entirely true.

This is one case in which one might bring up (again!) the famous Freudian quip that “sometimes a cigar is just a cigar,” which I mention, knowing Freud likely never said those words, and he definitely never wrote them. But it seems apposite here because the founder of psychoanalysis overanalyzed what he spent his time in Rome contemplating.

Freud thought he knew the faith of his Jewish heritage, and he thought he knew Moses (his last book would be Moses and Monotheism in 1939), but all along, he was a fantasist, always looking for and finding himself in whatever he observed. In this, he was obsessive. (He’s why Woody Allen has been in analysis for 50 years.) Freud was a remarkable writer, but a failed scientist.

Michelangelo was not the first to portray Moses with horns, but once he did, the motif became common in Renaissance and Baroque painting and sculpture, and has remained so to this day. The reason for the horns is rooted in Exodus 34:29:

When Moses came down from Mount Sinai, with the two tables of the testimony in his hand. . . .Moses did not know that the skin of his face shone because he had been talking with God.

His face “shone” because it was radiant or with rays of light (“qeren” in Hebrew). But in preparing his 4th-century Vulgate (i.e., Latin) Bible, St. Jerome decided qeren is best rendered as horned. Thus, for example, in the 1899 English version (Douay-Rheims), we get:

And when Moses came down from the mount, Sinai, he held the two tables of the testimony, and he knew not that his face was horned from the conversation of the Lord.

Biblical scholarship before and since notwithstanding, those horns were just too tempting for many artists, and they are very prominent in Michelangelo’s sculpture, completed in 1515.

I’m reluctant to analyze the sculpture, beyond noting that some art historians believe the muscular tension in the figure shows an angry man about to rise up to cast down the tablets because, in his absence, the restless Israelites had crafted a pagan Golden Calf.

I can’t help thinking the sculptor may simply have been angry at the late pope and the whole della Rovere clan.