Consider this: “In those early times of our American grandfathers and great-grandfathers, two prevailing visions dwelled above their lives. One was the spiritual design of national union which in the Civil War took so much bravery and sacrifice to secure. The other was the continental destiny of the United States which in the conquest and settlement of the West took so much work and love to fulfill.”

Bravery, sacrifice, work, love: these are not words one hears very often when it comes to contemporary accounts of American history, and certainly not of westward expansion. One is far more likely to hear about theft, exploitation, racism, and violence.

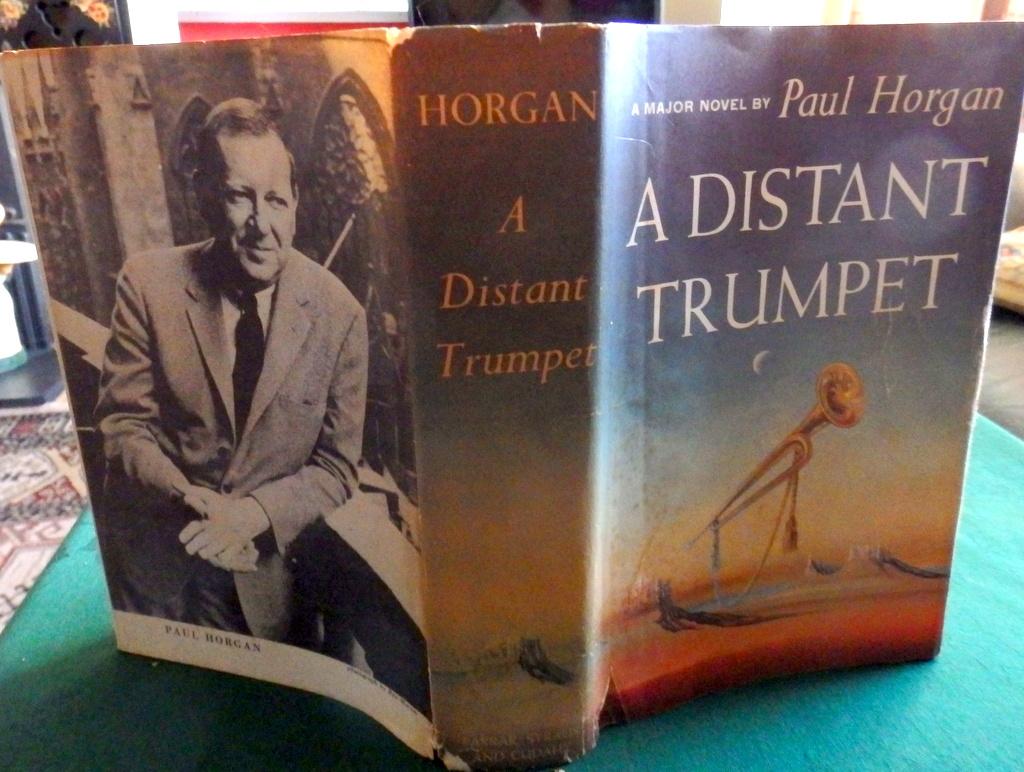

Yet this is how two-time Pulitzer Prize-winning Catholic author Paul Horgan begins his epic 1960 best-selling western A Distant Trumpet, a novel that traces the stories of U.S. army soldiers and their wives, as well as the Apache warriors they encountered in the final days of the American frontier. It’s a captivating saga, one that in its honest brutality rivals the greatest westerns of the American imagination, while in its optimistic portrayal of its protagonists offers a welcome (and implicitly Catholic) counter to a genre too often defined by nihilistic cynicism.

In his postscript, Horgan – who was made a papal knight by Pope Pius XII – cites a massive amount of primary and secondary source material for his story, including memoirs, U.S. Government publications of Congressional hearings and reports on Indian affairs and frontier troubles, indemnity claims, military policy and experience, and Surgeon General’s records. “This is a historical novel, which means that a period and a scene have been enriched – indeed, largely created – by general reference to known circumstances.”

What were those circumstances? U.S. Army officers of varying competence and motives, leading similar enlisted men, many first-generation immigrants from across western Europe, whose first language was not English. A young, idealistic officer is told he must “learn that the army is like any other human institution – it contains all kinds and descriptions of men, capable of every error, just like men on the outside.”

Enlisted men served on a dangerous and inhospitable frontier, often far from settled communities, and aware that fierce indigenous warriors freely roamed the wilderness.

Yet Horgan is also impressively knowledgeable about and sympathetic to Apache culture. He lauds their reverence for their ancestral lands and how their warriors possessed an ancient nobility and unquenchable courage. That ferocity sometimes manifested itself in horrific acts, such as torturing soldiers and settlers alike and mutilating the bodies of those they killed.

So terrible were Americans’ fear of the Apache that the few women on remote military installations – usually wives of officers and laundresses – had to learn to shoot; if they were in danger of being captured, they were told to use the bullets on themselves.

Nevertheless, reflecting an underlying Catholic ethic, many of the Anglo-American characters make an effort to treat Indians as human persons rather than subhuman savages. This sometimes occurs in circumstances when everything inside such Westerners inclines them to perceive American Indians as so primitive that they lack dignity or rights. (Horgan knew quite a bit about Anglo-Indian relations, winning a Pulitzer for his biography of Archbishop Jean-Baptiste Lamy, a 19th-century missionary to New Mexico.)

Horgan does not ignore the fact that the U.S. government and the Army often treated indigenous peoples miserably. Rather, as he explains, there were plenty of Americans who respected their native counterparts and also recognized that their own people were capable of great evil. One senior army officer declares: “Indian savagery and cruelty, ingenious and remorseless as they are, are but fragments of humanity’s general capacity for savagery and cruelty. Indians do not have a monopoly on these traits; nor do we white people have exclusive claim to virtue and enlightenment.”

Moreover, A Distant Trumpet certainly contains vignettes of a darker vision of the West, reminiscent of such literary masterpieces as Cormac McCarthy’s Blood Meridian. Horgan describes two Confederate gentlemen emigrating to Mexico, where they hope to find “vast properties, limitless riches, even patents of nobility.” They are murdered by a young American adventurer they had befriended. He, in turn, is overcome by Mexican criminals.

Yet perhaps what makes Horgan’s novel so singular is its ability to marry the dark barbarity of the West with moments of hopefulness and humanity, such as a pregnant mother pondering the new life she is soon to welcome into the world. The husband, in turn, feels a higher sense of chivalry as he reflects on his wife’s sacrifice and the child. The wife’s determination to stay at the fort for the delivery – even after learning of her husband’s earlier infidelities – portrays a degree of forgiveness and virtue largely entirely absent from contemporary westerns, which emphasize retribution rather than mercy.

A story with too little evil is saccharine and inhuman. But the reverse also departs from the reality of human experience, in which people, even under incredible duress, often choose the good. The newborn baby is baptized on the frontier by the Catholic wife of another officer. The West, writes Horgan, “brought people from both sides of the War together in a new purpose, and to those who went it presented danger, hope and a share in heroic creation.”

As one of the U.S. Army officers reflects before an impending battle with the Apache: “Did a man have to be as strong to deal with knowledge of himself as he did to put his power upon the world?” That is a far more complicated (and frankly Catholic) question than the typically simplistic and Manichean narratives of the Western genre.

It’s also one far more relevant to the struggles we face, as our principles are tested by great suffering and evil. “In skirmish or battle all occurs too swiftly to create philosophy by the moment. But if one brings one’s philosophy along, all is to show in its light, and struggle, goodness, evil, and sacrifice stand forth plain.”

A sentiment worthy of the Summa.