Most Catholics, even well-informed Catholics, if asked who were the great medieval saints would reply with a familiar list of names: Francis of Assisi, Dominic, Thomas Aquinas, Catherine of Siena. But one of the earliest among these great figures – and most conspicuous in his day – has, oddly, been almost forgotten in modern times. He was so obviously holy and multifaceted that Dante, in Paradiso, after meeting with hundreds of other saints and heroes, chose him to make the ultimate prayer to the Virgin Mary so that he, Dante, would be granted the Beatific Vision.

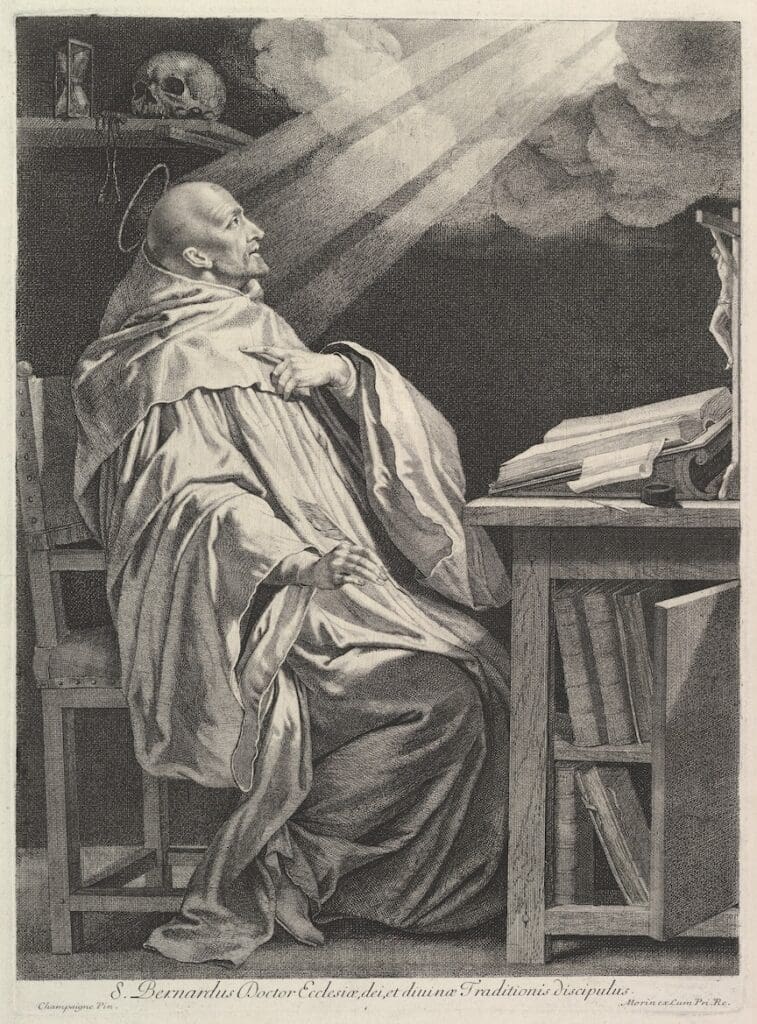

That forgotten saint is Bernard of Clairvaux (1090-1153), the Mellifluous Doctor, whose feast is today. We’re somewhat aware of Doctors of the Church again just now because of St. John Henry Newman’s nomination to that very exclusive body (he brings their number up to only 38). Some have been given special names because of what they did. Augustine is the “doctor of grace,” Aquinas the “angelic doctor,” Anselm the “doctor magnificus.”

Bernard is “mellifluous” because his words were regarded as flowing and sweet as honey. But in his lifetime, he was also a charismatic leader, builder, reformer, adviser to kings and other temporal rulers, and – in his role in helping to found the Knights Templar and the Second Crusade – could sting like a bee when the Church and Christendom needed to be defended (in his time, from militant Islam, which was then reconquering the Holy Land).

We tend to think these days that contemplative figures are otherworldly, that whatever virtues or progress that they achieve in the spiritual life have little, if anything, to do with our earthly grubbiness: messy politics, wars and rumors of wars, or even the multiple ways in which worldliness – sex, greed, ambition above all – corrupt religious institutions.

Bernard believed the opposite. That the spirit was essential to the right ordering of the world and keeping worldly things in their proper, secondary, place.

Even as Bernard wrote the most sublime spiritual texts (just read his commentary on the Song of Songs), he was equally adept at tackling the practical needs of his time. And he inspired others to follow him. Although he started as just another monk at the famous reform abbey of Cîteaux, it wasn’t long before he founded his own monastery at Clairvaux, which attracted numerous vocations and led, by direct and indirect routes to hundreds more foundings in the Cistercian reform.

The Church today is badly divided. But the Church in Bernard’s time was still worse. It faced the usual heresies among the intellectuals. (He gave Peter Abelard, among others, a pretty good smackdown.) The bishops in several places, even Paris, needed to be stirred up to defend the Church against the state (sound familiar?) – a task that he succeeded in almost miraculously. But worst of all, two popes were elected simultaneously in 1130, producing a schism that he was asked to resolve. Which he also did.

And all that amidst his efforts to make peace among various actors in France, Germany, and Italy – even to prevent pogroms against Jews (hence the common Jewish name Bernard, popular even today).

Writing to his patron Can Grande della Scala, Dante says that those who wonder whether it’s truly possible to ascend to the Beatific Vision should consult three texts: St. Augustine’s De quantitate animae, Richard of St. Victor’s “On Contemplation,” and St. Bernard’s On Consideration.

“Consideration” was a technical term in those days, akin to meditation, shading off into full-blown contemplation. The bulk of the work is advice to Pope Eugenius about how not to let practical matters eat up his soul. Dante had suffered under ambitious and unspiritual popes and princes, and doubtless resonated to passages such as, “Action itself certainly does not fare well unless preceded by consideration.”

But recognizing the proper scope of the practical underscores the primacy of the spiritual all the more.

This puts a question to all of us almost a thousand years later. We’re not the great St. Bernard. But we all have the dual task of pursuing holiness and, simultaneously, dealing with a world and a Church in tumult.

Almost no one would have thought in Bernard’s day that the High Middle Ages were coming. Yet they did, partly because of his efforts. There’s no reason why a similar renewal couldn’t occur even now if we seriously pursue spiritual disciplines even as we also confront our own forms of barbarism and decay. In fact, it’s precisely those painful conditions that spurred Bernard – and should inspire us – to redouble our commitment to faith and works.

Our friend, poet Dana Gioia, translated Bernard’s prayer to the Virgin in the last canto of Dante’s great poem. It begins with what seem to be logical contradictions; “Virgin mother,” “daughter of your son,” “humble and most high.” Yet it doesn’t just list things that appear to us irreconcilable, but resolves the tensions by gathering everything Dante had written about in his journey from earth to Heaven into a holistic unity:

Virgin mother, daughter of your son,

More humble and more high than other creatures,

The constant goal of the eternal plan,

You are the one who so raised human nature

That your Creator did not hesitate

To be created in your mortal flesh,

And in your womb was gathered all the love,

The warmth of which fills our eternal peace

And nourishes this flower as it grows.

For us in heaven you are the bright sun

Of charity at noon and to the living

You are the running fountain of their faith.

Lady, you are so powerful and great

That he who would seek grace and not seek you

Is one who would try flying without wings.

Your blessings do not fall only on those

Who ask for them, but many times they come

Freely to those who do not know their need.

In you is mercy, in you is pity,

In you is majesty, in you is gathered

All the good of all created things.

All the good of all created things. Mellifluous and the foundation of the practical, indeed.