A few years ago, I attended a conference given by a wise Benedictine abbot, who recounted an experience he had during a trip to the Orthodox monasteries on Mount Athos. What he described was an episode directly related to the veneration of sacred images in the Eastern tradition.

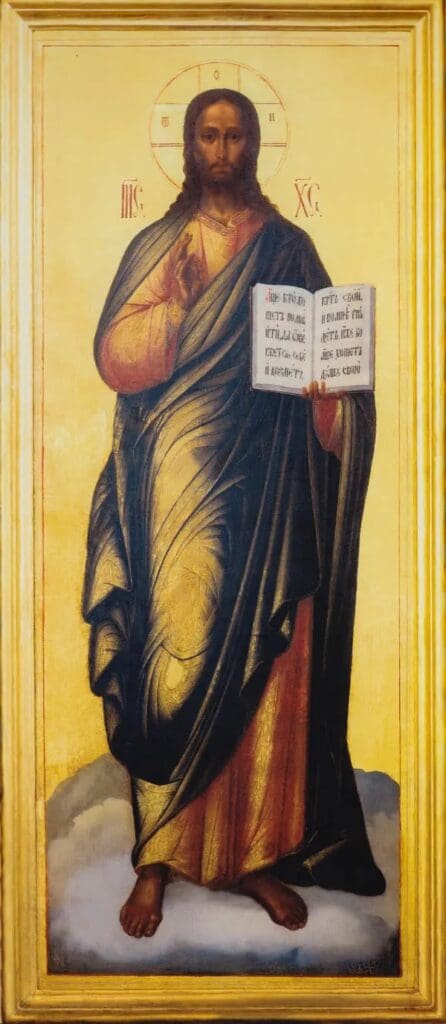

A father on pilgrimage entered a church, holding his little boy by the hand. With steady, slow steps, he approached an icon of Our Lord Jesus Christ. He bowed before it, made the sign of the Holy Cross, and kissed the icon. Then he lifted his little boy, who kissed Christ the Savior loudly, as one does when giving a kiss on his mother’s cheek.

The monk recalled this episode while emphasizing the naturalness of the gesture. We were all witnessing a true lesson in sacred manners, presented by someone who knew what it means to adore God the Son, represented in a holy image.

Against the iconoclasm of the Protestant reformers, the Church founded by our Savior Jesus Christ reacted with the most important event in its history: the Council of Trent (1545–1563). Amid its numerous sessions (twenty-five), the conciliar Fathers also discussed the role and value of sacred images. They reviewed the teaching concerning them, showing that there are two categories of religious visual creations. There are

• sacred images, which involve the representation of persons existing in the unseen world, and

• religious paintings, of a pedagogical character, which depict scenes from the earthly lives of holy persons.

There are, of course, many crucial “technical” differences between these two categories of visual representations. But perhaps the most important distinction, however, is the attitude one has before them.

“Sacred images” are always intended for worship. In other words, they truly place us in the presence of the persons represented. When we stand before an icon of Our Lord Jesus Christ, we must practice adoration with all the appropriate gestures. When we are before an icon of the Blessed Virgin Mary, we must practice hyper-veneration and its corresponding gestures.

As for angels and saints, they must be venerated with the gestures suitable to them. After nearly fifteen years of providing catechesis in many Catholic parishes, I can say that – unfortunately – such distinctions are unknown to most believers.

As a convert from Eastern schismatic Christianity – of which the father and his little boy in the abbot’s story were members – I noticed immediately when I began attending Catholic liturgies, the absence of gestures directed toward the holy persons represented in those statues and paintings that belong to the category of sacred images.

Over time, I attended Masses in Roman Catholic churches in which these were entirely absent. In Arizona, North Carolina, and New York, as well as in Italy and Scotland, I visited churches that seemed more like sports halls or auditoriums than sacred spaces. It’s no surprise that the appropriate gestures before icons, where these still exist, are missing. We can observe this, moreover, by comparing the Church’s two major catechisms.

The teaching about holy images is present both in the Roman Catechism (1566) and in the newer Catechism of the Catholic Church (1992). The essence of the teaching about icons is found, intact, in both. Here is what the Roman Catechism states:

The images of Christ, of the Virgin Mother of God, and of the other saints, are to be had and retained particularly in temples, and that due honour and veneration are to be given them; not that any divinity or virtue is believed to be in them, on account of which they are to be worshipped; or that anything is to be asked of them; or that trust is to be reposed in images, as was of old done by the Gentiles who placed their hope in idols; but because the honour which is shown them is referred to the prototypes which those images represent; in such wise that by the images which we kiss, and before which we uncover the head, and prostrate ourselves, we adore Christ; and we venerate the saints, whose similitude they bear. (Session XXV)

The relationship between the image – the representation – and the represented person – the prototype – is clearly emphasized. The Christian sacred image is a “window” through which we honor real, living persons who dwell in the heavenly Jerusalem.

The same teaching is repeated in the newer Catechism of the Catholic Church:

Basing itself on the mystery of the incarnate Word, the seventh ecumenical council at Nicaea (787) justified against the iconoclasts the veneration of icons – of Christ, but also of the Mother of God, the angels, and all the saints. By becoming incarnate, the Son of God introduced a new “economy” of images. The Christian veneration of images is not contrary to the first commandment which proscribes idols. Indeed, “the honor rendered to an image passes to its prototype,” and “whoever venerates an image venerates the person portrayed in it.” The honor paid to sacred images is a “respectful veneration,” not the adoration due to God alone: Religious worship is not directed to images in themselves, considered as mere things, but under their distinctive aspect as images leading us on to God incarnate. The movement toward the image does not terminate in it as image, but tends toward that whose image it is. (2131-2322)

Founded on the Council of Nicaea, both catechisms capture the essential. And yet, something is missing from the newer catechism: the mention of gestures – first and foremost the kiss – through which sacred images can and should be venerated. Is this merely an “oversight,” or the sign of a strange amnesia that could very well be a sign of a cooling of the love and worship owed to the holy persons in Heaven?

What is certain is that the new iconoclasm has made – and continues to make – victims.