They say of Julius II (pope from 1502 to 1513) that he did not choose his papal name in honor of his illustrious predecessor Julius I of some 1150 years earlier, but because of his esteem for Julius Caesar (100-44 BC). Maybe, although the pope’s birth name was Giuliano della Rovere, and Giuliano is a close cognate: Iulius in Latin and Giulio in Italian.

As much as any other pope, Julius II is responsible for bringing great art to the Vatican. The Sistine Chapel was built at the behest of Pope Sixtus IV, after whom it’s named, but it was Julius II who hired Michelangelo to decorate its ceiling and altar backdrop. The pope also brought in other esteemed Renaissance artists, among them Raphael.

Now, after a decade of restoration, the Vatican has reopened the Apostolic Palace’s Hall of Constantine (Sala di Costantino). The Hall is one of four rooms in the Palace that Julius II commissioned Raphael to decorate with frescoes. Collectively, they are known as the Raphael Rooms (Stanze di Raffaello).

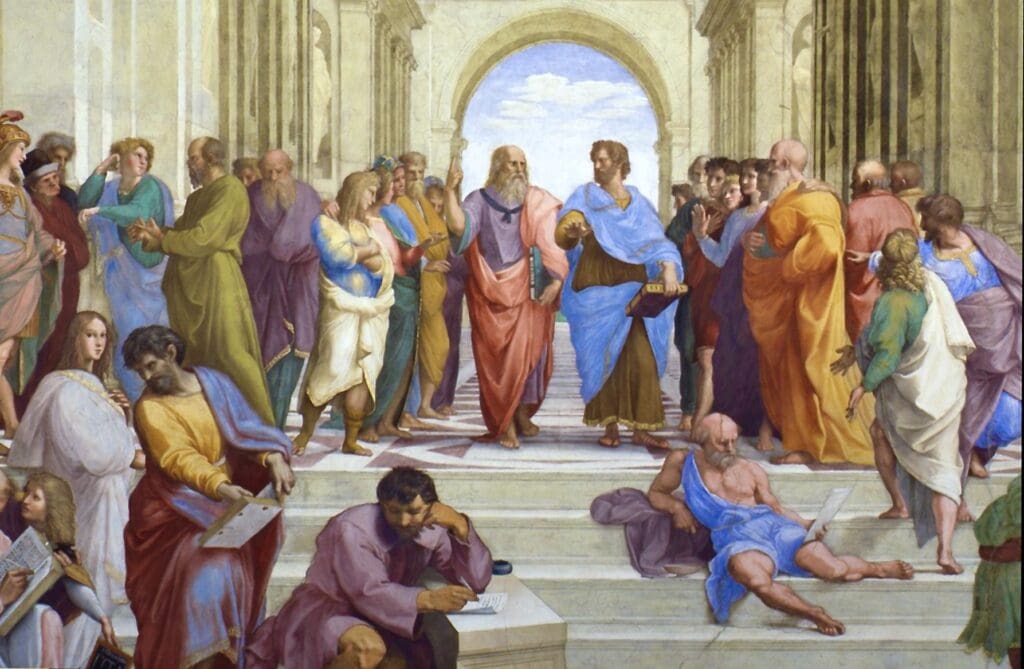

Raffaello Sanzio da Urbino was born in 1483. His father, Giovanni Santi, was also a painter, and Raphael trained with him and another very fine artist, Pietro Perugino, who is best known for his The Delivery of the Keys (Sistine Chapel, 1481-82), completed just before his future student was born. (One may see similarities between that work and Raphael’s The School of Athens, 1509–11, also in the Apostolic Palace).

We know Giovanni Santi and Perugino were fine teachers, because Raphael was considered a master at 17. At the behest of Julius II, Raphael came to Rome in 1508, where, until his death, he worked almost side by side with the great Michelangelo.

They were not friends, however. Michelangelo considered Raphael a plagiarist, a libertine, and a dilettante. There’s no question Michelangelo believed that Raphael imitated him. In one letter, the older man wrote that “all he had in art, he got from me.” That seems unlikely and an insult to Giovanni Santi and Perugino.

But why honor a Roman emperor in the Apostolic Palace? Because it was Constantine I who knocked down the barrier between his City of Man and Christ’s City of God. Christians went from being persecuted by Rome’s pagan emperors to being protected by Constantine’s Edict of Milan (313), allowing Christian worship to flourish.

Thus, we see depicted in the Hall of Constantine the highlights of the emperor’s life: The Vision of the Cross, The Battle of the Milvian Bridge, The Baptism of Constantine, and The Donation of Rome.

Briefly: In the 4th century, Rome had divided leadership that led to armed conflict. On the eve of a battle in 312 that would take place at Rome’s Ponte Milvio (still standing today), the then-pagan Constantine had a vision of the Cross. In his version of this miraculous event, Raphael did not use the famous Latin words In Hoc Signo Vinces (“in this sign conquer”) but its Greek equivalent, Εν τούτῳ νίκα.

The next painting shows the battle itself:

The battle won and the vision having been confirmed, Constantine becomes a Christian through baptism:

The final painting is of the emperor ceding temporal power to the pope:

The pope in Constantine’s time was Sylvester I, who is credited in the fresco with baptizing the emperor, but that’s untrue. The rite was likely administered by Eusebius of Nicomedia, an Arian priest, not to be confused with Eusebius of Caesarea.

What the newly converted Constantine might have thought when someone alerted him to the unorthodox beliefs of the Arians (rejection of the Trinity and the divinity of Christ), we can’t know. Perhaps the heresy of Arius seemed reasonable to the emperor.

But somebody put a bug in the emperor’s ear, which is why he convened the Council of Nicaea in 325, which gave us the Creed, and Arius a slap in the face, although only figuratively. (And that’s a shame because the image of Nicholas of Myra – THE St. Nicholas of Christmas fame – hauling off and striking Arius is such a good one, and especially popular among Orthodox iconographers.)

And it must be noted that Emperor Constantine was baptized only on his deathbed in 337, two years after the death of Sylvester I. This means there is a bit of woolgathering in Raphael’s The Donation of Rome. As the Vatican Museum explains:

The Emperor Constantine is depicted in the act of offering a golden statuette, symbolizing the city of Rome, to Pope Sylvester, in front of whom he is kneeling: on this episode (which turned out to be legendary) rested the legal foundations of the Church State and the temporal nature of the power of the popes themselves. (emphasis added)

One of those “legal foundations” is the so-called Donation of Constantine, the emperor’s imperial decree that gave authority over Rome and its empire to the pope. However, that document is an 8th-century forgery – one that the Church was happy to use in buttressing its authority during the Medieval period.

If a lie is told often enough, people, even good people, will believe it. The Donation’s authenticity was questioned early, and few believed in its validity by the time Raphael and his assistants were at work in the Hall.

I mention the assistants because Raphael did not do most of the work. He died suddenly on April 6, 1520, at the age of 37. (Thus the references to the “Circle of Raphael” above.)

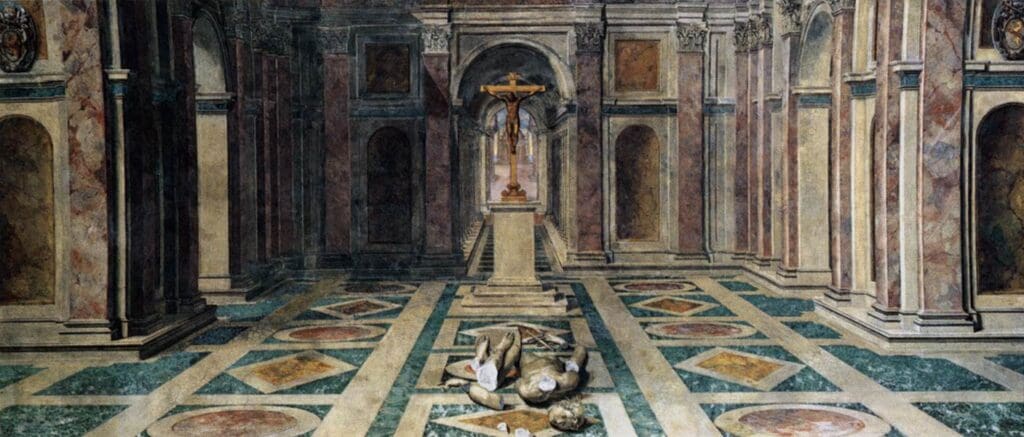

And there’s more in the Hall of Constantine than just the work of Raphael. On the ceiling is a remarkable fresco by the Sicilian artist Tommaso Laureti. Painted a generation later, the “Triumph of Christianity over Paganism” is vivid in its composition: a gold cross set upon a pillar looming over the statue of a toppled god, shattered into pieces, and referring to “the destruction of the pagan idols and their replacement with the image of Christ, ordered by Constantine throughout the empire.”