Stephen P. White

There is something fitting about the date of Thanksgiving. I don’t mean that there’s anything particularly special about the fourth Thursday of November except that it invariably falls in the last week of Ordinary Time. And so our secular holiday corresponds with the close of the liturgical year. This produces an interesting juxtaposition in which a celebration of God’s bounty and blessings is set amidst a liturgical barrage of readings about the end of the world.

Take, for example, the readings for today: Thursday of the 34th week in Ordinary Time. In the first reading, we see men break into Daniel’s home, denounce him before the king, and have him thrown to the lions. We know the story ends happily for Daniel, but not for his accusers or their wives or their children. “Before they reached the bottom of the den, the lions overpowered them and crushed all their bones.”

The Gospel for the day is taken from Luke, and it’s apocalyptic from start to finish. “Jesus said to his disciples: ‘When you see Jerusalem surrounded by armies, know that its desolation is at hand.’” and it gets worse from there: Woe to pregnant women, people falling by the edge of the sword, being trampled underfoot, or dying of fright.

The Lord promises to return in glory and exhorts the faithful to stand erect, but the whole scene sounds awful, and one gets the distinct sense that Jesus fully intends for it to sound awful. When the Son of God warns of “terrible calamity,” and “wrathful judgment,” and “nations in dismay,” it is prudent to take him seriously.

In the United States, of course, we generally hear the readings for Thanksgiving Day, not for Thursday of the 34th week in Ordinary Time, and these readings are much less likely to sour one’s stomach before the turkey is even in the oven. The readings for Thanksgiving Day are all about gratitude for God’s blessings.

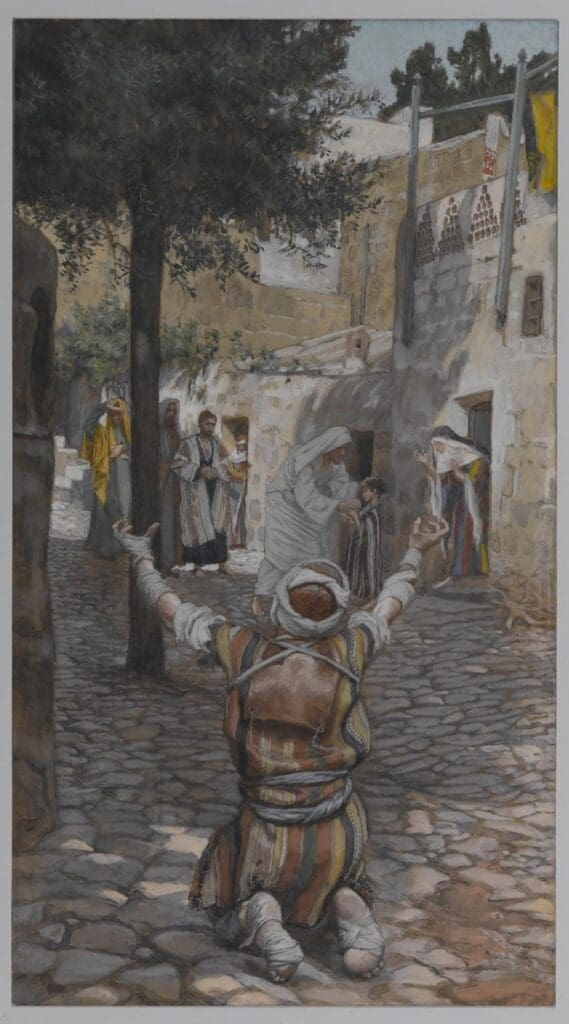

We hear from the Book of Sirach how the Lord tends the child even in the womb, and of joy and peace and the Lord’s enduring goodness. We hear from Paul’s first letter to the Corinthians how God pours out his grace and every spiritual gift. In the Gospel (also from Luke), Jesus heals ten lepers and the Samaritan alone among them returns to give thanks: “Stand up and go; your faith has saved you.”

No lions; no crushed bones; no terrible calamity or wrathful judgment. Just grace, healing, and glory to God for blessings bestowed.

This juxtaposition between these two sets of readings, the wide variance in tone, might seem jarring, even contradictory. But we Christians know that the futility of this world, which is passing away – both in the transience and material corruption we experience every day of our short lives, and in the tumultuous, terrible, no doubt awesome end to come – in no way negates the goodness of this world or of this present life.

These are extraordinary gifts, given to us by a loving God, for our use and enjoyment. He made this world for us, and He made us capable of enjoying it.

Of course, being a stiff-necked, ungrateful race, we tend to make a hash of these gifts. We worship the gift to the exclusion of the Giver. We lose sight of the proper end for which all these wonderful means are intended. We hoard and waste His gifts, both of which are species of ingratitude.

We even, some of us, teach ourselves to despise His gifts in a misguided attempt to compensate for our tendency to wantonness. Discipline in virtue is a good and necessary thing for everyone, and every saint is an ascetic in some fashion. The world may well hate us, but to hate the world in return is to underestimate the gratuity of its Maker, a slight against the magnificence of the Incarnation.

On that last point, the Advent season, which always follows Thanksgiving so closely, is above all a season in which we prepare to revel in the great mystery of the Incarnation – the ultimate rebuttal to the ancient heresies of the Gnostics and Manicheans. The world was not only made by a God who declared Creation “very good,” it was made in such a marvelous way that He could enter into it Himself. This world may be passing away, but it is also this same world into which was born the babe of Bethlehem.

And that is a delightful thought, even here at the end of the liturgical year, among the bare trees and shortening days.

As I said, the arrival of Thanksgiving during these apocalyptic days is fitting. Feasting at the end of the world might seem impious, spiritually adjacent to fiddling while Rome burns. Giving thanks ought not be reserved for times of peace and ease. Were the whole world burning around us, it would be right and just for Christians to give thanks to God for all He has done for us.

The world is passing away, and we can be content to let it go. We can give thanks to God for His gifts even as we offer them back to Him. Gratitude is not for the good times only, and whether the Mass readings of a given day speak of doom and travail or blessings and comforts, we respond alike, “Thanks be to God.”

I wish you a blessed and very happy Thanksgiving.

Michael P. Foley

Princeton Professor Emeritus Peter Singer occasionally makes the news with his radical opinions about ethics, such as a healthy pig having more of a right to live than a handicapped human being. Singer’s latest defense of animals, Consider the Turkey, describes the plight of the 46 million commercially raised turkeys killed and eaten at Thanksgiving. When the book came out in 2024, he published an op-ed in the New York Times arguing that we should end the Presidential Pardon of a turkey on the grounds that the turkey is not guilty of anything.

The Presidential Pardon is, of course, a joke, one that Singer does not seem to get. But one can forgive Singer’s dark mood after following him into the gross world of Big Food and Big Ag. Consider the Turkey reads like the nonfiction version of Upton Sinclair’s The Jungle. I wonder if Singer is surprised to see how much he has in common with Robert F. Kennedy, Jr. and the MAHA movement. As Pascal once observed, les extrèmes se touchent.

One need not buy Singer’s thin anthropology in order to sympathize with his concerns. The way that we harvest and process our food is indeed a problem; it is bad for our health, bad for our character, and bad for nature. But let us be honest: even if we fix these problems, we are still left with the basic fact that we must take life in order to preserve our own, even if we are vegetarian. In the words of Wendell Berry:

To live, we must daily break the body and shed the blood of Creation. When we do this knowingly, lovingly, skillfully, reverently, it is a sacrament. When we do it ignorantly, greedily, clumsily, destructively, it is a desecration. In such desecration we condemn ourselves to spiritual and moral loneliness, and others to want. (from “The Gift of Good Land”)

Berry would like to see a more “sacramental” interaction with Creation. I agree, but I would also like to see something more: I would like us to “earn” our place at the top of the food chain by making the sacrifice of, say, a turkey worth it.

To illustrate my point, I share with you a personal memory. One year a farmer-friend gave us one of his geese for our Christmas dinner. When my wife thanked him for his generosity, he replied: “Oh, not at all. It is an honor for this goose to end up on the Foleys’ table rather than to die of old age or be killed by a coyote.”

An honor. . . . But I am sure that if we had asked the goose, he would have told us that it was an honor he would be willing to forego, but nevertheless, it is an honor, an ennoblement, for the lower to participate in the higher. When goose flesh becomes human flesh, it becomes part of a higher reality, that which St. Paul calls the Temple of the Holy Spirit.

This is true even when goose flesh nourishes thieves and other scoundrels, for even the worst of sinners continue to bear the imago Dei, and their bodies continue to participate in that dignity. And the holier the person is, the truer this principle is: consider the singular honor bestowed upon the animals, like the Passover lamb during the Last Supper, that fed the Son of God when He was on earth.

This, at least, is how Saint Anthony of Padua thought about it:

When the heretics of Rimini, Italy refused to listen to him, the Saint went to the shore and began preaching to the fish, which assembled according to size in neat and tidy orders to hear him: little ones in the front, medium ones in the middle, and large fish in the back. Anthony told them to give thanks to the Creator insofar as they could, for God gave them food and shelter, blessed them at the beginning of creation (Gen. 1:19-22) and, unlike land animals, preserved them from the ravages of the Flood. Finally, they had the privilege of being food for the Lord Jesus Christ both before and after His Resurrection. The fish opened their mouths and nodded in assent. When the heretics witnessed this miracle, they threw themselves at Anthony’s feet and begged to be instructed.

Both science and common sense tell us that animals – including we rational animals – live off the deaths of others. Rather than bemoan this basic fact of life or try to circumvent it, we should live our lives worthy of these sacrifices.

Let us eat to keep the animal department of our nature functioning, and let us conduct ourselves in a way that our position as apex predators bears spiritual fruit. When we destroy and consume what is lower than us, let us live according to what is highest in us.

And this Thanksgiving, let us be grateful for this privilege and pray for the grace to live up to it, no matter how the turkey ended up on our table.