Richard A. Spinello

Controversies continue over the nature and role of women as modern society edges ever closer to embracing an androgynous anthropology. During the last Olympic Games, spectators were exposed to the surreal exhibition of biological males pummeling women boxers. Those who protested were informed that there is no scientific way to differentiate men from women.

The secular mentality has lost sight of what it means to be a woman. There are many reasons for this tragic exit of womanhood, but foremost among them is the negation of transcendence, which obscures the light that shines forth about the truth of our humanity. As Carrie Gress has pointed out, the poisonous influence of anti-Christian feminism has led to the “end of woman” because we have no answers to the question of what makes a woman a woman.

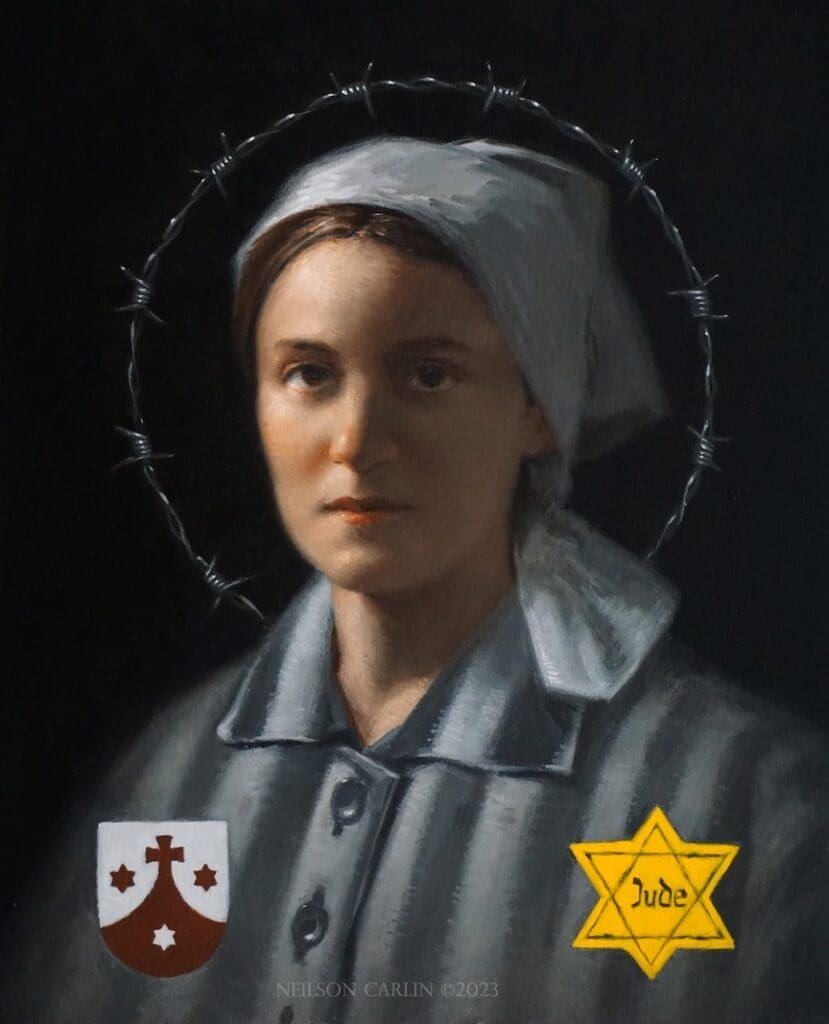

On this feast day of Edith Stein, Saint Theresa Benedicta of the Cross, it is fitting that we consult her work on these issues because of its reflective openness to the depths of human existence. If we want to reconstruct the idea of womanhood, her daring and intelligent book Woman is an optimal starting point.

The details of her life are well-known. She was a brilliant Jewish atheist who studied philosophy under the famous phenomenologist, Edmund Husserl. She converted to Catholicism after reading the autobiography of St. Theresa of Avila. Several years later she became a Carmelite nun. When the Nazis targeted Jewish converts in Holland, she was sent to Auschwitz, where she was executed on August 9, 1942.

After her dramatic conversion, she encountered the metaphysics of St. Thomas Aquinas, which made a deep impression on her philosophical development. She was not a Thomist in the strict sense, but her magnum opus, Finite and Eternal Being, is certainly Thomistically inspired. She found an original way to harmonize the modern philosophy of phenomenology with the medieval philosophy of Thomism.

Stein follows Aquinas by endorsing a hylomorphic anthropology, an old idea with an Aristotelian pedigree: the person is a natural and indivisible unity of a material body and a spiritual soul. The soul penetrates the body as it unifies all the different physical and spiritual aspects of each person.

In Woman, Stein’s main objective is to demonstrate the distinctive nature of womanhood that derives not just from the body but also from the soul. One’s sex is determined by the body’s given order informed by the soul, which comes into existence as already either male or female. Sexual differences, therefore, represent two irreducible ways of being a living, personal substance.

In declaring that there is a difference between the male and female soul, Stein parts company with Aquinas for whom the soul was the same for every member of the human species. For Aquinas, the soul becomes differentiated once it is united with a sexed body. But for Stein, the soul is different before it unites with and animates a male or female body, so that a person is feminine not just because of her body but also because of her soul.

Thus, Stein speaks about a “double species” because of the immutable differences between man and woman. Stein’s subtle anthropological vision has implications for understanding how egregiously transgender ideology undermines the profound body-soul unity of the human person.

Transgenderism is a rebellion against the finitude that permeates our being. As Stein insists, no one is the source of her own existence, but rather finds oneself as a being created by God, either male or female. If Edith Stein is right, both the body and the soul impose certain natural constraints on our choices and aspirations. Also, proponents of transgenderism would be asking us to believe that God blundered when he infused a female soul into a male body.

Stein’s anthropology becomes the foundation for her reflections on the nature of woman. Because they possess a different soul, women are different in kind from men, but how does that difference manifest itself in concrete ways?

Quite simply, what makes a woman a woman is her maternal vocation. A woman’s feminine traits, such as empathy, caring, and moral sensitivity, make her ideally suited for motherhood and marital companionship. A woman’s “body and soul are fashioned less to fight and conquer than to cherish, guard, and preserve.”

Women are also better protected from a truncated or one-sided view of others. And this is important because a woman’s mission involves understanding the total being in her care. While it is true that not all women will give birth to children, every woman is naturally capable of various forms of psychological or spiritual motherhood

Yet this sexual differentiation assumes a more fundamental unity. Men and women participate in a common human nature because they have the same ontological structure: a personal substance composed of a physical body animated by an intellectual soul. This commonality within which we uncover the distinction between men and women implies that they share similar creative gifts and talents.

According to Stein, “No woman is only woman; like a man, each has her individual specialty and talent, and this talent gives her the capacity of doing professional work.”

Thus, a woman’s natural vocation to marital companionship and motherhood should not preclude her work in other professions, especially those such as medicine and education that foreground her feminine gifts. At the same time, we must acknowledge the supreme dignity and excellence of motherhood and marriage that elevate this vocation among secular occupations.

Is Edith Stein’s provocative thesis about the feminine soul correct, or has her creative retrieval of Aquinas missed the mark? Do the asymmetries of sex go much deeper than the sexed body?

Regardless of how one answers these questions, we can agree that her voice should have a special place in the modern feminist chorus, for it is the clear voice of a faithful saint and philosopher who can liberate from obscurity the beguiling mystery of womanhood.

Elizabeth A. Mitchell, S.C.D.

Hurrying about gaping at our cellphones, we have become a society that no longer knows how to see. We prefer texting to eye contact, virtual reality to actual reality.

We have become essentially immune to our surroundings, unaffected by the beauty in front of us. But this failure to see causes us to become both individually and collectively impoverished.

Walking across London Bridge, for example, souls who are spiritually dead were observed by T.S. Eliot, who noted, channeling Dante, “I had not thought death had undone so many.” (“The Wasteland”)

The artwork is not dead, the sacred music is not dead, the architecture is not dead. We are!

When the Cathedral of Notre Dame de Paris burned, the world mourned the loss of a living, breathing entity. Our collective grief surprised us. Why did we feel the loss of a building so deeply? Modern man had assumed that the structure had been relegated to a cultural artifact. In actuality, the Cathedral was a life-giving fountain in ways we did not perceive. The life-power of Notre Dame cannot be extinguished. It is rather our souls which must be re-awakened to respond to its power anew.

Imagine the New York skyline without Lady Liberty, or the Parisienne nightscape with no Eiffel Tower. We wouldn’t be in Rome without the Colosseum; we are lost in London without her Bridge.

Our national and collective identities are imprinted with these artistic and architectural treasures. The artist, therefore, has a unique role in assisting what St. Edith Stein calls “the revival of a community by the world of values.”

The souls of the spiritually dead can be re-awakened to genuine soul-filled living by an encounter with beauty. The role of the artist in facilitating this awakening through the artwork is fundamental.

“Insofar as (a person’s life) precipitates in objective ‘works,’” Stein posits in Philosophy of Psychology and the Humanities, “it can become the common possession of the nation or of humanity, or it can exert influence upon the mind of one community or another and thereby upon the development of its character and the further course of its life.”

We might think here of the pervasive impact the talents of Sir Christopher Wren had on the city of London and the cultural revival of the British architectural landscape. Wren’s London emerged after the Great Fire of 1666 had destroyed much of the medieval cityscape. His works became what Stein would term “the common possession of the nation.”

Fittingly, Wren’s tombstone in St. Paul’s Cathedral, translated from the Latin, reads: “Underneath lies buried Christopher Wren, the builder of this church and city; who lived beyond the age of ninety years, not for himself, but for the public good. If you seek his memorial, look about you. – Si monumentum requiris, circumspice.”

Yet, while lauding the vital role of such artistic works, Stein also confronts the possible extinction of the cultural patrimony of civilizations. A civilization, she explains, has “created out of itself an inexhaustible fountain, as it were, from which it can always draw new powers.” But we can let these cultural fountains fall dormant.

The soul’s capacity to respond to their beauty can be temporarily switched off:

A branch of civilization can “wither away” while the nation to which it owes its existence lives on, and not only when the nation itself perishes. Then truly it’s not the civilization that’s dead – its life endures perpetually. Rather, it’s the souls upon whom the civilization should be bestowing life. Certain layers of their life are switched off. That the civilization isn’t dead is shown by the fact that it can undergo a “renaissance” at any time. It needs only to be discovered anew in order to become operative and bestow power.

For Stein, the infinite fullness of meaning revealed by the artwork is charged with potential energy, like food or firewood. The encounter of the human spirit with this potential energy converts it into kinetic, active power within us. Exposure to beauty is, therefore, life-giving. When a work of literature reinvigorates our soul, when a piece of classical music renews our spirit, we are imbibing this life-power of beauty.

In her own life, Stein intentionally drew upon such “propellant powers” from artistic sources. Under the strenuous burden of her academic work, she sought renewed strength from the works of Shakespeare:

If anything could sadden (my mother) in those days, it was the enormous workload I was carrying. . . .Only at about ten at night would I begin preparing the following day’s classes. If, while doing so, I became so fatigued that I could no longer grasp anything, I would read a bit of Shakespeare. That so renewed my vitality that I was able to begin again.

So, in a woefully spiritually decrepit age, such as ours, there is hope, great hope! Beauty has life-power. And we can be renewed and resurrected to soul-filled living by each encounter. Stein’s artistic vision is acutely needed today to teach us how to encounter beauty, be transformed and uplifted by it, so that we, in turn, may transform and uplift others and be in communion with God.

As Wren’s tombstone declares, look about you, everyone! Recognize, receive, and carry forth your cultural, intellectual, and spiritual patrimony. By doing so, you can re-awaken your soul, the souls of this generation, and those to come, to life-giving fountains of the good, the true, and the beautiful.

[Adapted from Elizabeth A. Mitchell’s St. Edith Stein’s Aesthetic. Beauty and Sanctity: Masterpiece of the Divine Artist, with a Preface by Cardinal Raymond Leo Burke, published by Gracewing, UK.]