November, Native American History Month, will rightly bring out remonstrations against the injustices of the 1830s, but to understand what happened we should start with the Proclamation Line of 1763, a British attempt to separate American colonists (who would live east of the Appalachians) and Native Americans (told to stay west).

The direct impetus for England’s order was Ottawa Chief Pontiac’s rebellion, which British soldiers ended at considerable expense. American independence did not change the preference of American leaders for geographic separation. Each of the first eight U.S. presidents, while in office, favored pushing Native Americans west.

In 1791, George Washington said he wanted a “Chinese wall” to keep apart whites and natives. That year, the United States and the Cherokee Nation signed the Treaty of Holston, by which Cherokee ceded some land and received from the U.S. a “guaranty” that they could retain all their other land. In 1802, though, President Thomas Jefferson promised the Georgia legislature that if it relinquished state claims on the land that became Alabama and Mississippi, the federal government would buy out Cherokee control of any property within the borders of Georgia “as soon as such purchase could be made upon reasonable terms.”

This was in essence an early version of eminent domain. But what if officials and owners did not agree on what was “reasonable”? Like someone who sells the same cow twice, Jefferson was handing two dueling groups control over the same land. Following the Louisiana Purchase in 1803, Jefferson urged visiting chiefs to give up their land and move to what would become the state of Arkansas. The deal would supposedly be voluntary, with Jefferson officially assuring chiefs that “your lands are your own, my children, and they shall never be taken from you by our people.”

Following battles during the War of 1812, however, President James Madison wanted to segregate the two races. A treaty negotiated partly by Andrew Jackson in 1817 pushed along the process. It all seemed so logical, as President James Monroe said in approving that deal and a further treaty in 1819: “The hunter of savage state requires [more land] than is compatible with the progress and just claims of civilized life, and must yield to it.” Novelist James Fenimore Cooper, clergyman Jedidiah Morse, and missionary Isaac McCoy also favored the racial divide.

Problems emerged, as one might expect. One was that many Native Americans did not want to leave their ancestral lands. Many were willing to give up their “savage state” for one or more of three reasons. Some found farming better to feed their families than hunting. Some wanted to be more acceptable to white culture. Some became Christians and found the settled life around a church better for their spiritual development.

Yet another problem: White settlers were moving into Arkansas, despite federal “Keep Out” signs. One senator said, “You had just as well pretend to inhibit the fish from swimming in the sea.”

So what if Natives didn’t want to go west? What if others took the land reserved for them? Even as federal officials kept pushing Native Americans to go to Arkansas, Cherokee who had moved into Arkansas were being pushed farther west, into what is now Oklahoma. Missionary Charles Kingsbury, who had won the trust of the Choctaws and accompanied them to treaty meetings, saw how U.S. commissioners engaged in “Whiskey Negotiations”: Get Choctaw representatives drunk.

By 1829, Georgian politicians said their state had been patient long enough. They passed laws depriving the Cherokee of all rights. They pushed Andrew Jackson to formalize what every president since Jefferson had urged: All tribes should move west of the Mississippi. Jackson in his March 1829 inaugural address said tribes should receive generous payments for their land, compensation for cattle, title to land west of the Mississippi, and “paternal and superintending care” thereafter. One influential missionary society, the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions, opposed Jackson’s plan.

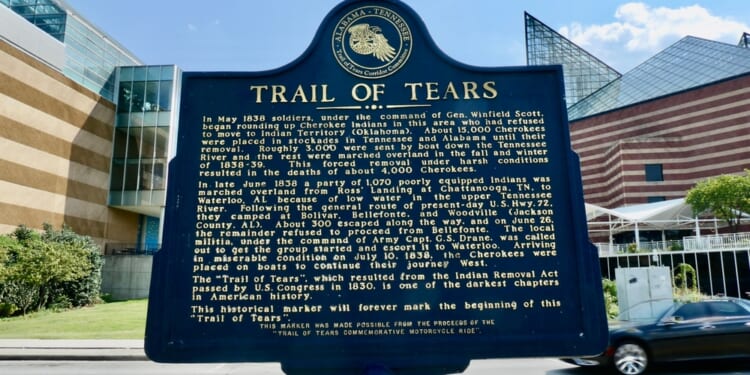

Jacksonians in Congress introduced in 1830 what became known as the Indian Removal Act. Congress would appropriate sufficient funds so Cherokee and other tribes could travel west and get land in what is now Arkansas and Oklahoma. Jackson declared: “This emigration should be voluntary, for it would be as cruel as unjust to compel the aborigines to abandon the graves of their fathers, and seek a home in a distant land. … Our conduct toward these people [will reflect on] our national character.” Jackson allies echoed that sentiment. Michigan governor Lewis Cass, for example, said, “No force should be used. … Indians shall be liberally remunerated.”

In a Senate packed with celebrities such as Henry Clay, Daniel Webster, and John C. Calhoun, a little-known first termer from New Jersey, Theodore Frelinghuysen, eloquently led the opposition. He scoffed at the conceit that the Cherokee would leave voluntarily: “When mercenary inducements fail to win them, force and terror may compel them. We shall have no difficulty, the agent assures the war department. Sir, there will be one difficulty, that should be deemed insurmountable. Such a process will disgrace us in the estimation of the whole civilized world. It will degrade us in our own eyes, and blot the page of our history with indelible dishonor” [emphasis added].3

Frelinghuysen traced the growth of the “Indian removal” idea for decades:

It is not intended, Sir, to ascribe this policy exclusively to the present administration. Far from it. The truth is, we have long been gradually, and almost unconsciously, declining into these devious ways, and we shall inflict lasting injury upon our good name, unless we speedily abandon them. … Do the obligations of justice change with the color of the skin? Is it one of the prerogatives of the white man [to] disregard the dictates of moral principle, when an Indian shall be concerned? …

Sir, if this law be enforced. I do religiously believe that it will awaken tones of feeling that will go up to God—and call down the thunders of his wrath. … How shall we justify this trespass to ourselves? Sir, we may deride it, and laugh it to scorn now; but the occasion will meet every man, when he must look inward, and make honest inquisition there. Let us beware how, by oppressive encroachments upon the sacred privileges of our Indian neighbors, we minister to the agonies of future remorse.” [emphasis added]

Those italicized words show that Frelinghuysen, who went on to be a losing vice presidential candidate on the Henry Clay ticket in 1844, was prophetic. Clay in 1830 added his emotional touch: “The United States stand charged with the fate of those poor children of the woods, in the face of their common Maker, and in presence of the world.”

Nevertheless, the Senate voted 28–19 for removal. The House of Representatives vote promised to be closer. Secretary of War John Eaton emphasized the importance of public relations: He advised the governor of Georgia to keep from doing “anything which might wear now the appearance of harshness toward the Indians.” Georgians should “unite with the Federal Government in avoiding even an appearance of practiced injustice towards the uncultivated and unhappy children of the forest.”

Evarts from the missionary board, not taken in, pleaded for honesty: “If the Indians are removed, let it be said in an open and manly tone, that they are removed because we have the power to remove them, and there is a political reason for doing it; and that they will be removed again, whenever the whites demand their removal, in a style sufficiently clamorous and imperious to make trouble for the government.”

Eaton’s response was not manly: “Nothing of a compulsory nature to effect the removal of this unfortunate race of people has ever been thought of by the president.” But Jackson did not dance with lies for long. He said publicly, “It will be painful for them to leave the graves of their forefathers, but what do they do more than our ancestors did or our children are now doing?” Privately, Jackson said the move would be voluntary only in this sense: “Build a fire under them. When it gets hot enough, they’ll move.”

Pennsylvania Representative James Buchanan said he and others were against “using the power of the government to drive that unfortunate race of men across the Mississippi.” It would all be voluntary. Sure. Many other Members of Congress did not believe him. Some cited War Department correspondence about ways to intimidate reluctant Native Americans.

Representative Davy Crockett said the treatment of the Cherokee had been “unjust, dishonest, cruel, and short sighted in the extreme.” He said he had been “threatened that if I do not support the policy of removal, my career will be summarily cut off.” That’s what happened: Crockett, his political career ended, eventually had a brief career in Texas, at the Alamo.

Representative Joseph Hemphill of Pennsylvania thought more information was essential. He wanted Jackson to appoint “three disinterested commissioners” to investigate the trans-Mississippi region and make sure the removal plan would work. The House vote on Hemphill’s proposal for a one-year delay was 98–98. Speaker Andrew Stevenson cast the deciding vote: No. No waiting. After more arm-twisting, the House voted 102–97 to approve Jackson’s plan.

Georgia leaders did not want any delays. When a Georgia court condemned to death for murder a Cherokee named Corn Tassel, the Cherokee asked the U.S. Supreme Court whether Georgia had jurisdiction. The court ordered Georgia to appear and explain why its verdict should not be overturned. Georgia responded by immediately executing Corn Tassel.

When the Supreme Court led by John Marshall ruled in another case that the Georgians did not have sovereignty over the Cherokee, states-rights advocates united with Jackson in ignoring the decision. Jackson probably never said what Horace Greeley two decades later attributed to him—“John Marshall has made his decision; now let him enforce it!”—but that was his message.

The Indian Removal Act became evidence for the expression “God is in the details” (which originated in the 19th century) and a variant, “The devil is in the details” (which emerged in the 20th). The Choctaw were the first to find out, from 1831 to 1833, what the details of moving 15,000 people against their will to a land across the Mississippi would be like. Some moved in winter by steamboat amid heavy rainstorms. The ice-clogged Mississippi and a lower-than-expected river in Arkansas caused delays and an unloading of the passengers 90 miles short of their destination. They ended up camping in the cold. Others were trapped in Mississippi swamps or halted by impenetrable canebrakes and swollen rivers.

Blizzards plus a cholera epidemic turned the trip into a trail of tears that was fatal for one-sixth of the travelers. It was also an eye-opener for accountants in Washington. Congress had appropriated $500,000 for a start on “Indian removal,” and the Jackson administration asked Congress for $3 million to move all the eastern tribes. The cost for the Choctaw alone, terrible as the experience was, came out to $5 million (about $165 million now).

The most infamous trail of tears was that of the Cherokee. It began when Jackson, with his mix of realism and racism, sent a letter to Cherokee leaders on March 16, 1835: “You cannot remain where you now are. Circumstances that cannot be controlled and which are beyond the reach of human laws, render it impossible. … Deceive yourselves no longer. … Shut your ears to bad counsels.” A minority of the Cherokee agreed and assented at the end of 1835 to what became known as the Treaty of New Echota.

Most of the Cherokee, though, opposed it. The U.S. Senate then had to decide whether to affirm the treaty. President John Quincy Adams had refused to recognize a treaty signed by a minority of Creeks in 1825. The Senate had turned down a treaty negotiated by one small band of Cherokee in 1834. John Ross, officially the principal chief of the Cherokee, planned to head to Washington with hopes to negotiate a new treaty, but the Georgia militia temporarily imprisoned him in a cabin that featured the decaying corpse of a hanged Cherokee dangling from the rafters.

Just as the House of Representatives barely gave approval in 1830, so the Senate barely gave two-thirds approval five years later to the New Echota treaty, on a vote of 31–15. One of the Cherokee protests stated: “Our cause is your own. It is the cause of liberty and justice. We have learned your religion also. We have read your sacred books. Hundreds of our people have embraced their doctrines. … We are indeed an afflicted people! … Spare our people!” To no avail: The Cherokee deadline became May 23, 1838.

In 1836 Major William Davis, assigned to make a list of all the Cherokee who would emigrate, told Lewis Cass, who had become Secretary of War, that the treaty was “not sanctioned by the great body of Cherokees” and was opposed by “nineteen-twentieths of them.” David said the Cherokee are “a peaceable, harmless people, but you may drive them to desperation.” His plea produced a sneer from Wilson Lumpkin, the new governor of Georgia: “Nineteen-twentieths of the Cherokees are too ignorant and depraved to entitle their opinions to any weight or consideration.”

Members of the Creek tribe in Alabama and the Seminole tribe in Florida went to war in defense of their land and lost. In 1836 and 1837, the army pushed 15,000 Creek into Oklahoma: As many as one-fourth died along the 750-mile route now known as the Creek Trail of Tears. The Cherokee remained peaceful. Nearly 500 Cherokee left on steamboats well before the 1838 deadline. They arrived in three weeks, with no deaths on the way. Six hundred of the more affluent Cherokee went overland, with their own supplies and arrangements.

Most of the Cherokee, though, waited. They had published a newspaper that counted 10 Cherokee-owned sawmills, 31 gristmills, 62 blacksmith shops, and nearly 6,000 spinning wheels and plows. After adopting a “white” style of life, after promises that any move west would be voluntary, they did not believe they would be forced out. Opponents of removal ended up making the process worse. Some congressional opponents tried to fight by not making appropriations. Fine, some Jacksonians replied: Cherokee starvation is on you.

The first general in charge of preparation, John Wool, saw confusion but reported to Washington that “impossibilities will be made possibilities.” Not exactly. Wool anticipated needs and ordered the purchase of 7,000 blankets, 4,000 pairs of shoes, and 4,000 yards of assorted cloth goods from New York to distribute among poor Indians. The War Department said no, because the Secretary of War, told to make the move as inexpensively as possible, had not authorized the purchase. Wool complained and gained reassignment to the U.S.-Canada border.

Major General Winfield Scott took over. Wanting the Cherokee to be transported by steamboat, he created three embarkation spots along the Tennessee River. He hired steamboats to go from the Tennessee River to the Ohio, then to the Mississippi, then on the Arkansas River toward northeastern Oklahoma. Steamboats would pull 130-foot-long keelboats, each with a 100-foot- long two-story house. Each story would have four rooms, 50-by-20 feet, with windows and stoves.

All very logical? On May 10, 1838, Scott assembled 60 Cherokee leaders and told them: “Cherokees! The President of the United States has sent me with a powerful army to cause you, in obedience to the treaty of 1835, to join that part of your people who are already established in prosperity on the other side of the Mississippi. … My troops already occupy many positions in the country that you are to abandon, and thousands and thousands are approaching from every quarter, to render resistance and escape alike hopeless. … The desire of every one of us is to execute our painful duty in mercy. [At the embarkation spots], you will find food for all, and clothing for the destitute.”

All very reasonable? Move thousands of people against their will over a thousand miles of river, forest, and swamp: What could go wrong? President Martin Van Buren late in the process realized more time was needed to get things right. Secretary of War Joel Poinsett proposed to the Senate a two-year extension and informed Governor George Gilmer of Georgia. Word spread among the Cherokee of a stay of execution. Many believed the kindly federal government would not roust them. They were wrong. Gilmer said that Georgia would accept no delay and that state forces would take matters into their own hands if federal forces did not show up.

Van Buren and Poinsett’s effort backfired. Fake news spread through the Cherokee: The deadline would be extended for two years! They were surprised when soldiers arrived on May 26 and at gunpoint drove them toward wooden stockades, not even giving them time to pack clothing, bedding, cookware, and other items. Scott, feeling “painful anxiety,” kept telling soldiers to be humane. Some were. Scott watched how Cherokee arriving at one of his depots were “half-starved, but refused the food that was pressed upon them. At length, the children, with less pride, gave way, and next their parents. The Georgians were the waiters on the occasion—many of them with flowing tears. … I had never witnessed a scene of deeper pathos.”

Eyewitness James Mooney described that pathos:

Families at dinner were startled by the sudden gleam of bayonets in the doorway and rose up to be driven with blows and oaths along the weary miles of trail that led to the stockade. Men were seized in their fields or going along the road, women were taken from their wheels and children from their play. In many cases, on turning for one last look as they crossed the ridge, they saw their homes in flames, fired by the lawless rabble that followed on the heels of the soldiers to loot and pillage. So keen were these outlaws on the scent, that in some instances they were driving off the cattle and other stock of the Indians almost before the soldiers had fairly started their owner in the other direction.

Years later a Georgia volunteer recalled, “I fought through the civil war and have seen men shot to pieces and slaughtered by thousands, but the Cherokee removal was the cruelest work I ever knew.” It got crueler: A terrible drought made rivers unnavigable and left the land routes without drinking water. Scott agreed to stop the forced emigration until September, but stockades meant for days were inadequate for months. Whooping cough, dysentery, measles, cholera, malaria, and dysentery hit the Cherokee.

Movement in the fall brought more sometimes-fatal terrors. One soldier who worked as an interpreter wrote:

In the chill of a drizzling rain on an October morning I saw them loaded like cattle or sheep into six hundred and forty-five wagons and started toward the west. … Many of these helpless people did not have blankets and many of them had been driven from home barefooted. … They had to sleep in the wagons and on the ground without fire. And I have known as many as twenty-two of them to die in one night of pneumonia due to ill treatment, cold, and exposure.

In 1841, John Quincy Adams, who 15 years before had favored voluntary removal, said the use of force would be “among the heinous sins of this nation, for which God will one day bring them to justice.” That, and slavery.

(This essay is an edited excerpt from Marvin Olasky’s Moral Vision: Leadership from George Washington to Joe Biden.)