Readers of books, and specifically fantastic books by Charles Williams and other Inklings, are summoned.

I do not like them as much as I should, for I have never been a fan of fantasy literature, and I note that among the Inklings, only J.R.R. Tolkien is a reliable Catholic. But C.S. Lewis is almost a Catholic, and the other two I have read are largely sympathetic. I wouldn’t put any of them on the Index.

Williams was the first I discovered. I haven’t fully discovered Tolkien even yet, though devoted types have upbraided me. Only Lewis is what I would call the preachy type, to whom I am naturally allergic. In a sense, Owen Barfield is the antidote to Lewis, though as an anthroposophist and translator of Rudolf Steiner, my trust in him is not unqualified. Let me just say that, like Lewis, I very much like him.

Yes, Tolkien. I should have been reading by now, but my aversion to hippies when I was young and impressionable kept me away. Tolkienists may be nice people, but I am not a nice person.

That is perhaps why I was drawn to Charles Williams, who by reputation was not a nice person. C.L. Wrenn (another Inkling), for instance, suggested burning him at the stake for his views, or something equally warm. While none of the Inklings were vegetarian when making arguments, this drew some blood.

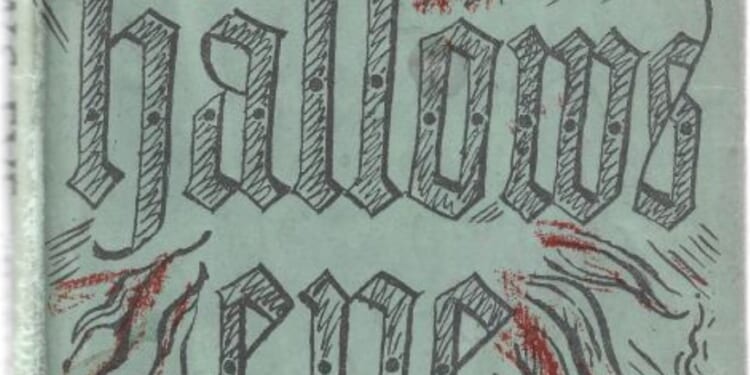

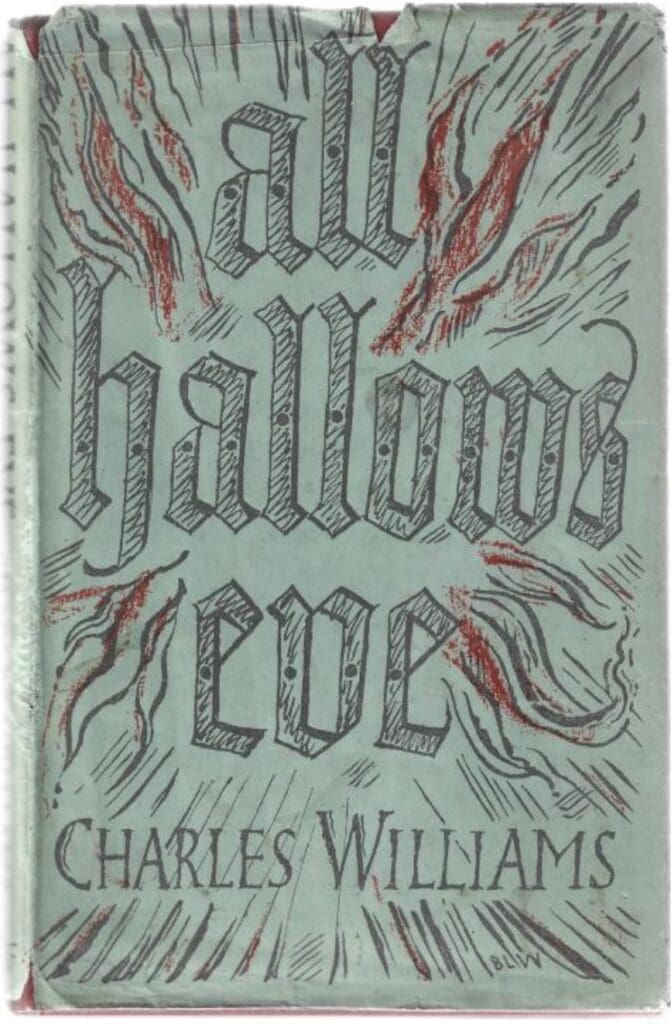

It is ALL HALLOWS’ EVE today, and I have been rereading the novel thus entitled by Williams. It was his last, and as he died just a few days after Hitler, recent accusations of anti-Semitism against him are not really plausible. The worst you could say is that his Antichrist character is Jewish, but English-speaking intellectuals were not plunged into Holocaust reporting until later in that year, 1945.

The novel opens with the death of a young woman, told from inside. It was the sort of thing that was happening when the book was published. Airplanes were crashing, here, there, and everywhere, making death slightly more common than it is today. And Christians will know that death has supernatural implications.

Williams didn’t avoid them. His plot, which develops out of the young woman – Lester Furnival – gradually realizing that she is dead, and then wandering through post-mortal London or the City of God, with her also late companion, Evelyn. Interactions between dead and living are presented from both sides.

All Hallows’ Eve, the seventh and concluding novel in Williams’ remarkable series, deserved its place as one of Messrs. Faber and Faber’s more reprintable books, reissued in America with a preface by T.S. Eliot. It was Eliot who tagged Williams as the author of “spiritual thrillers,” a special genre.

For remarkable people like Dante Alighieri and Charles Williams were capable of writing such things. It is easy enough to write a thriller, but making a narrative “co-inhere” with a spiritual plot is difficult, on the scale of impossible. One must rise to classical heights; casual contact just won’t do.

But Williams, too, was a shameless “religious nutjob,” whose wanderings into, for instance, Jewish mysticism, can be distressing to the modern secular reader, for it suggests the universe is uncomfortably large, and there may be more in it than a remorseless secularism could tolerate.

Indeed, Williams was also quite aware that Jesus Christ was a Jew.

Curiously, it was the reliable J.R.R. Tolkien who delivered the most subtle criticism of Williams’ processions into the occult. But Williams goes there to a purpose, and comes back with important news from the supernatural realm. It is that both good and evil are present at large, and will both be encountered when one invades either nature or supernature unprepared.

A good life is, of course, the best preparation, and the Godhead, in the person of Jesus Christ, is the best companion.

Williams was, by nature, a theological writer, whether his genre is theology or not. He can be entertaining, but even this is meant to a theological end.

When he is writing of Dante – and his book, The Figure of Beatrice, seems to me one of the best English commentaries on Dante – he is the ideal “romantic,” founded in Godly intellect, not irresponsible emotion.

Williams was an exponent of the theological doctrine of Perichoresis, which was Latinized as “Circumincession,” meaning the sublime “dance” of the Triune God. And Williams almost anglicizes this as “Co-inherence.” But he extends it beyond the Three Persons of the Trinity, into apparently many worlds that are interpenetrating.

Indeed, Augustine understood something like this in Latin, even before the Greek Fathers invented technical terms, and one should use this as an excuse to explore Augustine’s De Trinitate.

The Holy Spirit is required in the understanding of divinity. The implications were never simple or commonplace.

Williams extends this to all relationships in love, and All Hallows’ Eve reveals it in an immortal love story between a husband and a wife, suddenly separated by death. Death is indeed, controversially, the means by which their love is enacted.

This argument was raised earlier in The Figure of Beatrice, Williams’ theological tract on Dante’s Beatrice, where earthly love co-inheres with divine love, and becomes the very introduction to the divine.

The almost tedious quality of the mortal life that Williams’ characters step out of, through the deus ex machina of death in an airplane wreck, becomes their “Hallowe’en.” There are two worlds adjoining, and each haunts the other.

Williams makes himself sometimes difficult to read by indulging in arcana and esoterica, which may not interest the theology buffs, like me. We can, however, understand why all that contributes, in his novel, to the importance of an Antichrist character.

It’s because the battle between good and evil is happening, and it is a battle in the heavens as well as on earth. Christ will be the victor in both places, but down here it appears to be a close-run thing.