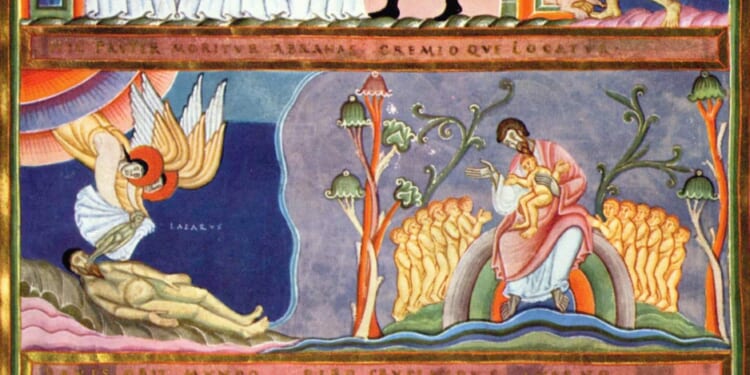

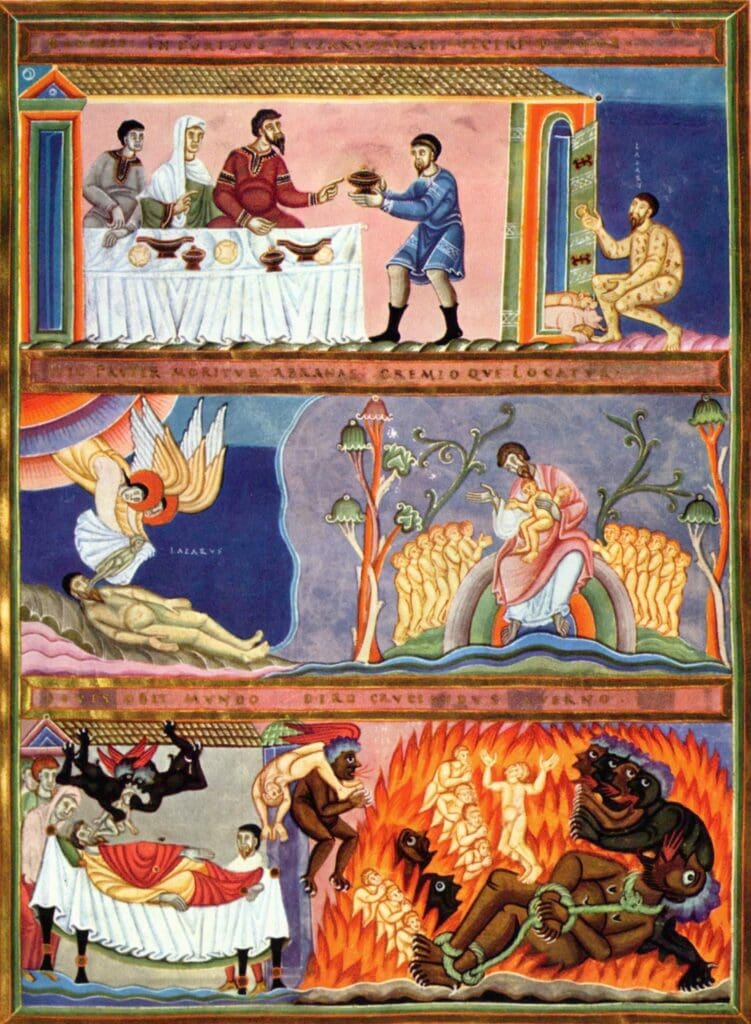

The haunting story of the rich man and Lazarus (Luke 16:19-31) is perhaps best understood in reverse, through the lens of where we find them at the end of the story. The status of each in the afterlife – the rich man’s suffering and Lazarus’s peace – reveals the reality of who they are. Without the trappings and clothing and disguising of this world, we see the rich man’s poverty and Lazarus’s wealth. We see most keenly the peril of riches.

It’s a parable about the danger of wealth. Not about the evil of created goods or possessions. Worldly goods obviously have their place. God created the material world to show forth and communicate His glory. We are to use the goods of Creation to glorify Him and to benefit others. Our Lord is not a Marxist, and property is not theft. So, the problem is not the rich man’s wealth per se.

But we would be foolish to think that there is no danger in wealth. In a fallen world, created goods take on an outsized importance. We come to trust in them rather than in their Creator. Indeed, they demand a kind of allegiance, as the rich fool discovered. (see Lk 12:16-20) This is why our Lord never praises wealth but only warns us against its dangers.

The first danger is intemperance. Our fallen nature inclines us to use our goods not for the glory of God and the benefit of neighbor but for our own comfort and luxury. So the rich man pampered himself. He “dressed in purple garments and fine linen and dined sumptuously each day.” So in the first reading, Amos rebukes the indulgent – “Lying upon beds of ivory, stretched comfortably on their couches” – who “drink wine from bowls and anoint themselves with the best oils.” (Amos 6:1, 4-7)

Their possessions have become an end in themselves, not the means by which they glorify God and do good to others. Intemperance leads us to use God’s gifts not for their purpose but for our own indulgence. The glutton eats only for pleasure and not for the good of his body. The lustful man seeks sex only for gratification and not for procreation or union.

Intemperance leads inevitably to complacency. Again, the prophet Amos: “Woe to the complacent in Zion!” This complacency is a kind of numbness and blindness, a deadness of the soul to nobler and higher things. It’s hard to raise one’s heart and mind when the belly is weighed down by rich food and drink.

So the rebuke from Amos is not only for luxury but for its effect, because it has rendered them numb to what is important. They “are not made ill by the collapse of Joseph.” That is, they don’t care about the suffering of their own people. So also in the Gospel, the rich man doesn’t even notice Lazarus. There’s no mention of any interaction between them. His wealth has blinded him to the very existence and suffering of a fellow man at his doorstep.

This complacency is revealed most of all when the rich man begs to return to his brothers and warn them, lest they suffer the same fate (as they seemingly had similar wealth). Abraham answers, “If they will not listen to Moses and the prophets, neither will they be persuaded if someone should rise from the dead.” Something kept them from listening to – from hearing – Moses and the prophets. Indeed, their wealth and luxury numbed and blinded them to the witness of Scripture, and it would make their minds resistant even to one risen from the dead.

Wealth numbs us not only to other people but also to the truth. Attachment to created things keeps the mind pinned down. Clarity of thought requires detachment from worldly goods. Again, the parable of the rich fool shows us how the mind of the wealthy is focused on maintaining and increasing material goods rather than on permanent things and eternal truths.

It’s said that Aquinas once visited Bonaventure in his study and asked which book gave him such great theological insights. Bonaventure pointed not to a book but to the crucifix as the source of his insight. That’s more than a pious story. It reminds us that detachment from the world is necessary to see all things clearly, the world included. There’s a reason all great reforms in the Church begin with poverty. Wealth blinds us. Detachment clears the mind to see what needs to change and frees the will to do it.

Complacency leads finally to grave sins of omission. The rich man didn’t do any harm to Lazarus. There’s no indication that he stole from him or cheated him in any way. He didn’t make fun of Lazarus or kick him while he was down. And that’s just the point. He didn’t do anything. Lazarus was suffering at his door – not in some far distant land or even down the road – and the rich man did nothing. The effect of this grave sin of omission is easily summarized: If you don’t care for the poor, you will go to Hell.

To avoid that fate, we need to return to the view of the rich man in Gehenna. What brought him there was intemperance, complacency, and finally neglect. May the Lord deliver us from wealth’s tentacles, so that we can clearly see and serve Him in the poor.