I must confess that I have watched the BBC’s six-part mini-series adaptation of Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice multiple times. As a video adaptation of a novel, it’s about the best I’ve seen though, but if you read the book you’ll see from the first sentence that it has its share of problems. In the video, Elizabeth Bennett speaks the famous first sentence of the book, “It is a truth universally acknowledged, that a single man in possession of a good fortune must be in want of a wife.” But in the novel, it’s the narrator’s, Miss Austen’s snarky comment on marrying for money thereby setting the tone for her entire story.

The video version also creates the difficulty of picturing the characters. Colin Firth is, at this point, Mr. Darcy whenever I reread Pride and Prejudice. I picture Jennifer Ehle as Elizabeth Bennett and David Bamber as the smarmy Mr. Collins. Good for the BBC’s talented casting team; bad for the reader who when reading the book is cheated in the use of his or her imagination.

Movies Modernize Classics, Every Time

Similarly, I’m sorry to say, I picture Austen’s heroine in the novel Emma as Gwyneth Paltrow and the characters in The Lord of the Rings pretty much as they are in the movies, characters that pale when compared with those Tolkien wrote about. Aragorn Son of Arathorn was not a post-modern weenie struggling with his identity, thank you very much.

And if you haven’t read the trilogy, you probably didn’t even notice the important missing pieces or the 21st century blather introduced into what is an essentially Medieval tale.

We Like Pictures and People More Than Words

Why not? Because despite the fact that it’s hard to quantify, research indicates that the human brain processes images some 60,000 times faster than it processes written text. The result, according to Trevor Throness of The Professional Leadership Institute is that video is, “easier to interact with, bypasses your cognitive mind and drives straight to your emotions, and both favors and encourages lazy thinking.”

Video images can and do slip into our minds and hearts without our thinking about them and evaluating them. It’s not that we can’t think about them — I’ve been doing that from the beginning of this column — it’s that thinking and reasoning about the images requires an extra step and extra effort. But how often do we rush to the next set of video images without pondering what we just saw?

Throness goes on, “Reading on the other hand is interactive. You have to form mental pictures and focus on translating shapes on a page into ideas in your mind. The medium makes you a stronger, more disciplined thinker regardless of the content.”

Reading Trains the Brain. Images Can Trick It

Note: “You have to.” Reading demands that we use our imagination and our reason. If my Stream column makes no sense, you’re on it right away. If I read it to you aloud or if I get on stage and perform it as a video with lights and music, I could hide the fact that it makes no sense.

In part ten of the still timely 1976 video series, How Then Shall We Live, Christian thinker Francis Schaeffer and his team hired actors to portray a confrontation between police and protesters. They filmed the same action twice using two different camera positions, different film editing, and different narrations. In the first depiction, the police were clearly at fault for using brute force to put down a peaceful demonstration. In the second, the protesters were clearly violent rioters and a threat to the police who did all they could to avoid violence.

“We staged this scene,” Schaeffer comments, “we filmed it to show how television can tell any story it wants to tell…. The nature of TV [that is, videos] is such: we see it with our own eyes, we naturally look at it as if it were objective truth.” And this was in 1976, long before the kinds of video tools and techniques available today.

Of course, books can mislead as well. The Communist Manifesto written by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels in 1848 has by this time mislead billions of people and caused untold suffering and the deaths of hundreds of millions. And, as I’ve indicated, videos and movies aren’t all bad. I watch them.

Nonetheless, we Christians are “people of the Book.” We know the Living Word by reading, studying, and contemplating the written Word. “Do not conform to the pattern of this world,” wrote St. Paul, “but be transformed by the renewing of your mind” (Romans 12:2). To do that, we need to put our reason to work and we put reason to work as we read, not as we watch. As Tony Reinke, Senior Teacher at Desiring God, wrote in his book Lit: A Christian Guide to Reading Books:

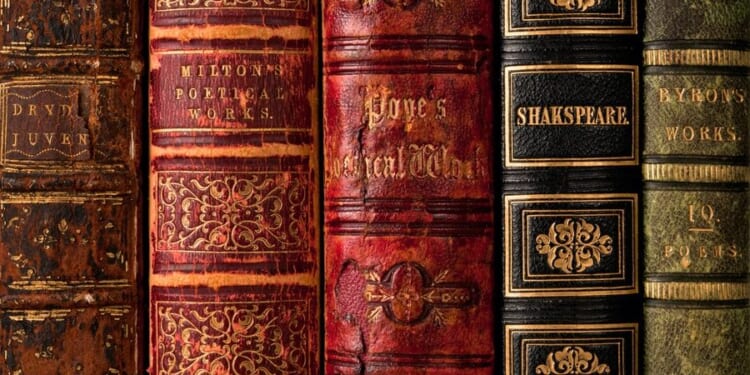

In a world so easily satisfied with images, it’s too easy to waste our lives watching mindless television and squandering our free time away with entertainment. We have a higher calling. God has called us to live our lives by faith and not by sight—and this can mean nothing less than committing our lives to the pursuit of language, revelation, and great books.

I could not agree more.

James Tonkowich is a freelance writer, speaker, and commentator on spirituality, religion, and public life. He is the author of The Liberty Threat: The Attack on Religious Freedom in America Today and Pears, Grapes, and Dates: A Good Life After Mid-Life. He is Instructor Emeritus at Wyoming Catholic College.