To hold in one’s hands a book like Josh Hammer’s Israel and Civilization: The Fate of the Jewish State and the Destiny of the West is the kind of privilege that comes with residency in the civilized West. Envious minds populating much of the rest of the world fail at development, despise the Jewish people (the two usually go hand-in-hand), and obscure Jewish history.

Israel and Civilization is a manifesto—both a historical account and a call to action. It creates a theoretical foundation for a Jewish-Christian coalition to defend the West from the wicked troika of wokeism, Islamism, and global neoliberalism.

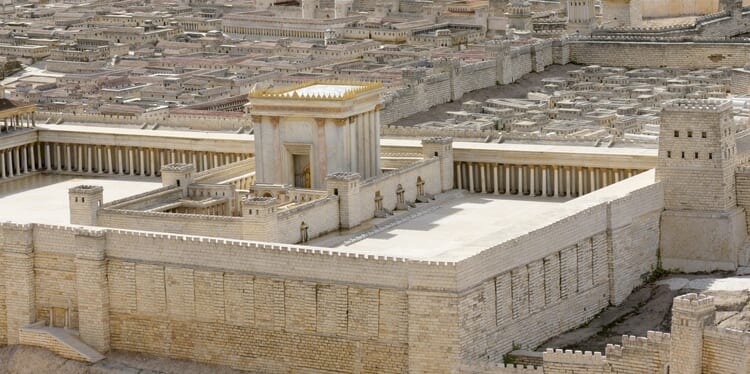

Hammer reaches back thousands of years in history to ground the Anglo-American political tradition in Hebrew moral teachings. The ancient Jewish idea of One True God to whom each individual answers, he explains, conditioned the soil for our moral, social, and cultural flourishing.

Despite subscribing to the conviction that all humans answer to One God, Hammer is not a universalist—he doesn’t believe that a single mode of social organization applies to every culture. He rejects the neocon naiveté postulating that democracy can be exported to the far corners of the world, just as he categorically opposes the similar Communist call for worldwide revolution. He’s a particularist who celebrates his own unique heritage, both Jewish and American, in defiance of the meddling NGOs and what he calls the “DEI left and Nietzschean right.”

He doesn’t get muddled in relativism either—he’s not an “anything goes” guy. Nor does he feel the need to frame his worldview in secularist terms. Instead, he takes the Torah as the prime source of guidance and inspiration. This time-proofed way of thinking enables him to create a framework for moral judgment.

Although the Jewish people, Hammer explains, are obligated to sanctify God by following the 613 mitzvot (commands), those expectations apply to Jews alone—that’s the particularist Jewish part. It doesn’t mean that the nations of the world are free to do as they will—the Creator gave the Ten Commandments and before that the seven Noahide Laws by which all the mankind must abide. After all, man was designed in the image of God and therefore possesses a certain God-given capacity to conform to moral norms outlined in these divinely ordained rules. As Hammer explains:

This belief in the inherent holiness of the mankind, which flows naturally from God’s revelation at Sinai and the establishment of a unique relationship between man and man’s Creator high above, is a foundational, overarching principle for what we today call Western civilization.

Hammer contrasts this revealed truth to the pagan worship of “the ‘rational’ human mind and/or hedonistic self-indulgence of the human ego, denying a higher authority and a transcendental calling.” He is not interested in simply dissing hedonism—that would have been too easy for a conservative writer—but the tension between faith and reason is a definite theme in the book.

Reason alone fails to make perfect sense of God’s revealed truths. We don’t know why God doesn’t want Jews to wear garments made of both wool and linen, Hammer observes. But to embrace revealed truths is to accept an authority higher than oneself that regulates our modes of conduct. He explained how in a Jewish context the Enlightenment, or the attempt dating back to the 18th century to structure society based on reason alone, weakened traditional bonds.

Yet the American system of governance is inspired by the Enlightenment—and it’s been a success. In contradistinction, Hammer cites John Adams’s famous adage that the American Constitution “was made only for a moral and religious people.” Judeo-Christian tradition is the unspoken assumption, the secret ingredient that allows this large and complex society to work neatly.

Naysayers notwithstanding, politics are rooted in religion and morality, and Hammer shows that “political Hebraism” has a storied history in Anglo-American societies. His background in law enables him to reconstruct the history of concepts borrowed from the Jewish Halachic tradition, like stare decisis, or assigning weight to previous rulings. He explains that our nation was founded by philo-Semites and Zionists. And if we have a clause prohibiting a religious test for public office in our Constitution, it was written with Jews in mind. To interpret it as an endorsement of atheism is a mistake.

Access to this type of knowledge should not be taken for granted. My children were fortunate to learn about the contribution of Jewish people to civilization from their public middle school textbooks in California, but in the Soviet Union, where I grew up, ancient Israelites were written out of world history. The USSR was of course an atheist, or more accurately a pagan, polity. It was also anti-Semitic and antizionist. It was, moreover, rooted in Marxist dialectical materialism. Karl Marx viewed the struggle between classes—slaves and masters in antiquity and the proletariat and bourgeoisie in modernity—as the sole acceptable paradigm for understanding historical narrative. Learning alternatives to this reductionist approach was an act of rebellion, a treasured underground activity.

In my case, my late father gave me “the Talk” about Jews in history when I was in my early teens. He wasn’t a believer, so he told me that Jews invented God and that the Bible is our national epic of which I should be proud.

The Soviet annulment of Jewish history was not limited to religious flashpoints like the Ten Commandments. Jewish contributions and Jewish experience generally were excluded from the mainstream Soviet account. The most infamous example was Babi Yar, the ravine near Kiev where in 1941 over the course of two days the Nazis massacred 34,000 Jews. The Great Patriotic War, as World War II is known in that part of the world, was understandably the mainstay of Soviet propaganda, but the Holocaust was hushed up. Soviet authorities refused to put a monument in Babi Yar—just as they declined to acknowledge that anything out of the ordinary happened to the Jewish people in that conflict.

Resistance to the Soviet regime often adopted philo-Semitic attitudes and Judeo-Christian religious themes. If Soviet propaganda obscured Jewish history even as the First World embraced it as a part of its ideological lineage, dissidents made common cause with the Jewish refuseniks. They felt it was a moral thing to do and that it brought them closer to the West.

The USSR saw itself as the true heir to the Enlightenment, but it became one of the greatest failures of the 20th century. It’s not just that despite their best and most ambitious attempts (a planned economy and all), it wasn’t a logically ordered society. Conspicuously missing from their scheme was the moral and religious dimension that Adams considered the key to America’s success. Instead of personal responsibility before a higher authority, the Soviets anchored themselves in Marxist dogma and the pagan collectivism of mir, or the Russian peasant community. And if the Tenth Commandment warns humans not to covet, the premise of socialism is to make sure that nobody has it too good.

Not unlike the USSR, the anti-Semitic and antizionist forces in the U.S. today are notably non-Western. Hammer talks of the woke left and the Nietzschean right, but—and I take an issue with his analysis here—both are often indistinguishable and informed by alien trends.

Take for instance Sephora makeup artist Huda Kattan. The Kansas-born entrepreneur of Iraqi descent contracts with the retailer famous for promoting women, sexual minorities, and people of color and is beloved by left-wing Gen Z girls. Yet she recently recorded a rant accusing Jews of starting all wars. That’s the thesis of Henry Ford’s The International Jew—and an inspiration to Adolf Hitler.

It’s often said that anti-Semitism and antizionism bridge the gap between the left and the right ends of the political horseshoe, and that’s quite true. However, what is more relevant in this case is that the beliefs Kattan expressed are mainstream in the Arab world. She is likely parroting the ideas tossed around the dinner table in her house.

The West also has a long history of anti-Semitism, but the information war impairing the contemporary Jewish-Christian understanding in this country is suspiciously foreign in its origin. The anonymous accounts redpilling American youth on social media are often located in Pakistan—so one of the most severely underdeveloped countries on earth is defining based for Gen Z. The envious anti-Semitism they sell as “traditionalism” might be ordinary elsewhere, but it’s novel stateside. It’s but another face of globalism.

Moreover, there is the substantial Qatari influence in public and private spheres. And then there’s former Fox host Tucker Carlson who went solo with the help of the New Jersey–born Pakistani-Iranian venture capitalist Omeed Malik. The Pundit’s reports from Moscow last year came across as if he were reading the Russian script.

In defiance of these significant powerful influences, Hammer offers many reasons why a Jewish-Christian alliance to save the West would be beneficial to both parties. He includes some conventional arguments like security cooperation and sub-replacement birth rates, offering that Israel is the only developed nation boasting healthy fertility.

Yet, in the end, it’s faith, not some lofty calculation, that informs the foundation of our civilization; and that faith, be it Judaism or Christianity, originated in the Land of Israel. Contemporary America is at a fork in the road. We can concede to the envy and resentment so common around the world—in which Jew-hate is an essential feature—or we can double down on our exceptionalism.

Make what you will of the fact that the high point of American supremacy was marked by philo-Semitism. Or that the Christian president with Jewish grandchildren has made it his life’s work to restore that supremacy. But it might just be divinely ordained.