The Catholic Project at The Catholic University of America (where I serve as executive director) has just published the results of a new major survey of American priests. The study builds on our past research (here and here), giving a clearer picture of the American presbyterate as it currently stands and hinting at what the future might hold for the Church in the United States.

This new survey provided an opportunity for a follow-up to the 2022 National Study of Catholic Priests, examining the well-being of our priests, their levels of burnout, confidence in their bishops or religious superiors, and the like. Since every participant in this 2025 study also participated in the 2022 study, we are able to track any changes longitudinally.

Our previous studies showed that our priests were, by and large, flourishing. Happily, our new data confirms that American priests are flourishing at levels well above the average for the general population.

This result is neither controversial nor surprising, but it should not be overlooked. Men who enter the priesthood tend to flourish. It’s not all wine and roses, of course (more on that in a minute). But whatever concerns priests have, whatever challenges they face, should be understood against this backdrop: on the whole, American priests are thriving.

That said, there are points of real concern. Many priests (44 percent of diocesan priests, 31 percent of religious priests) show signs of burnout. And 45 percent of younger priests (those ordained since 2000) say they are expected to do too many things that go beyond their calling as a priest. The same percentage of that cohort shows elevated indicators of loneliness. Older cohorts of priests are doing significantly better by both measures.

Diocesan priests’ confidence in the leadership of their bishops remains low (52 percent), but has risen slightly (up from 49 percent) since our 2022 study. Confidence in the U.S. bishops generally shows a similar trend, rising from 22 percent in 2022 to 27 percent in 2025.

Our previous study showed that a priest’s perceived alignment with his bishop on political and theological matters correlated with the degree of confidence that the priest had in his bishop’s leadership. As our report shows:

A far greater predictor of a priest’s confidence in his bishop is whether the priest agrees with the statement, “I feel that my bishop cares about me.” 72 percent of diocesan priests who said that their bishops care about them express confidence in their bishop, whereas among priests who did not say that their bishop cares about them, only 10 percent express confidence in their bishop.

This new finding is perhaps unsurprising, but it strongly underscores the highly personal nature of the relationships between bishops and their priests.

A second broad objective of this study was to get a clearer sense of the actual pastoral priorities of American priests. What do our priests see as the greatest pastoral challenges facing the Church in the United States?

This included a chance to drill down a bit on what our priests think about the Synod on Synodality, to what degree their parishes participated in the Synod, and how it changed, if at all, their ministry.

American priests were not very enthusiastic about the Synod on Synodality. Only 39 percent thought the Synod was not a waste of time (37 percent positively agreed that it was a waste of time); only 28 percent felt they were fully included in the Synod, and only 25 percent agreed that the Synod had been helpful for their ministry. So much for that.

But when it comes to synodality in practice, American priests are already engaged in many of the “synodal practices” recommended by the Synod, even if priests don’t connect those activities with “synodality” or the Synod itself.

So, for example, 85 of percent priests with parish assignments reported that their parish has a pastoral council or similar body that plays an important role in decision-making; 75 percent said that they always involve parishioners in prayer and reflection before making significant decisions in the parish; 69 percent offer training or support to help lay people take an active role in the Church’s mission beyond the parish; and 65 percent report having changed a parish practice or decision based on lay input within the past year.

As for the top pastoral priorities of American priests, they are: youth and young adult ministry, family formation and marriage prep, and evangelization. Each of these was listed as a priority by 94 percent of respondents.

These were followed closely by “poverty/homelessness/food insecurity (88 percent), Pro-life issues (87 percent), and immigration/refugee assistance (81 percent).

Climate change, synodality, and LGBTQ ministries scored comparatively low, being seen as priorities by 54 percent, 50 percent, and 48 percent of priests, respectively. Only 26 percent of priests said access to TLM should be a priority (59 percent said it should not).

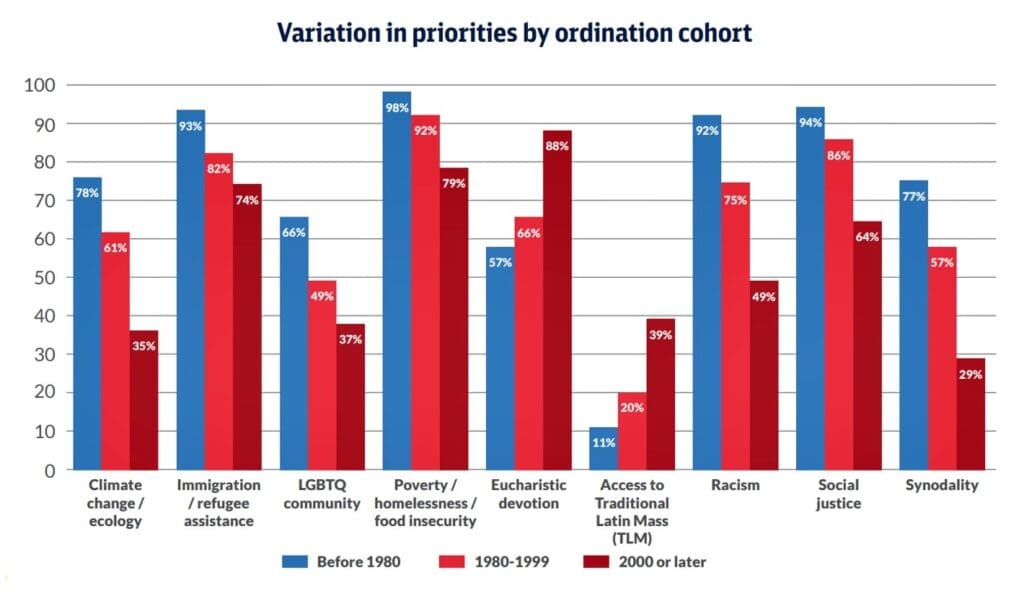

These priorities varied significantly between older and younger cohorts of priests, as the chart below demonstrates.

Less than half of priests ordained since 2000 see racism, LGBTQ issues, climate change, or synodality as pastoral priorities. Priests ordained before 1980 are more likely to see each of those issues as a higher priority than Eucharistic devotion.

There is little to be gained in overstating the significance of these differences – and none to be gained by dismissing simply priests because of their age or the views of their contemporaries. But the long-term implications of these data are significant, particularly when one considers that less than a quarter of our priests were ordained before 1980, while those ordained since 2000 make up 42 percent. And that number is growing.

The American presbyterate is united in its support for the family, for young people, and for evangelization. It shares a broad commitment to the poor and to migrants. And it is equally eager to defend life from its beginning to natural end. None of this seems likely to change in the years to come. At the same time, a commitment to Eucharistic devotion and to traditional (if not Traditionalist) liturgy appears likely to grow.

I, for one, find that very encouraging.