In His discourse at the Last Supper, Christ teaches the Apostles about three related themes: knowing and seeing God, loving God, and being one with God. He holds out these three as different aspects of a single phenomenon.

Christ tells the group, “Where I go you know, and the way you know.” Thomas insists they don’t know where Christ is going. Christ assures him, “If you had known me, you would have known my Father. And henceforth you do know him, and you have seen him.”

Seeing and knowing are linked. What it is to know, the field of epistemology, is one of the most vexing areas of philosophical investigation.

When Philip still asks to be shown the Father – to see Him – Christ explains that He is in the Father, and the Father is in Him. To see Christ is to be shown the Father. See the Father and me as one, Christ seems to exhort them. And if Philip’s faith can’t fully grasp that identity, he can at least see the visible works Christ has performed.

In the dialogue Statesman, Plato seems to offer a choice similar to what Christ gave Philip. The wise “visitor” to Athens explains that “it is not painting or any other sort of manual craft, but speech and discourse, that constitute the more fitting medium for exhibiting all living things, for those who are able to follow; for the rest, it will be through manual crafts.”

If we can’t understand things with our speculative or theoretical intellect, we can get some understanding through concrete things made with our hands: Plato’s equivalent of “if you can’t understand with your mind, understand through works.”

And this isn’t a mutually exclusive choice. Consider the Benedictine precept of “ora et labora,” or “pray and work.” Mental acts (including monastic study) and manual acts provide a way of contemplative life, to encounter the greatest truth.

In Plato’s Republic, Socrates describes our knowledge of reality as like a line divided into four parts: “imagination” that takes in sensory images; “belief” about what the objects whose images we detect really are; “thought” that works with mental concepts such as geometric shapes that we draw from images of objects; and finally “understanding” that seeks to grasp the highest realities, the forms or divine intellectual ideas of truth, beauty, and goodness that transcend the time-matter world.

Images and physical objects lie in the domain of the visible, the things that we can sense. The “objects” of mental concepts and the forms are in the intelligible domain that we know through reasoned speech.

The intelligible domain on this divided line, says Socrates, is actually the larger part of reality, of what is – larger than the reality we see and sense.

Taken together, Socrates and Plato in these cases are telling us that what we know with our intellect is greater than what we can sense. They draw the link between seeing and knowing. For all of us, knowledge begins in the senses. For some of us, our knowledge will be drawn mainly from those senses. For others (philosophers), the higher intelligible truths will be accessible through the speculative intellect.

Christ, though, will give the Apostles faith in Him and His Father as the key to the highest truths. Plato wasn’t far off – he didn’t have Judeo-Christian revelation to work with. Jesus adjusts Plato’s approach to make the highest truths available to everyone, and he completes the idea that the full truth is much bigger than the visible world, the works and objects that we see around us.

So the problem of seeing and knowing the greatest good has been around for a long time, before the light of Christ brought us a way to understand it more deeply. What about being one with God?

Aristotle saw “being one” as a problem of knowing. In his De Anima (On the Soul), he studies the question of how the rational human soul knows something. He claims that “actual knowledge is identical with its object.” And he calls the soul the “place of forms.”

His meaning is not entirely clear, to me at least, but he seems to suggest that for us to know an object, we must become that object. We do so by knowing its form, or the principle that makes it what it is. When I know a tree’s form, I am “informed” and become, in a sense, the tree. I don’t become a tree in the “literal” sense, because I don’t share its matter. The tree is still a distinct thing apart from me.

But Aristotle’s insight is that to know something is have its form become part of you. We are very close to what we know. Modern philosophy would introduce a greater distance between things we know and ourselves, challenging this Aristotelian notion and separating us from the world.

Aristotle gives knowledge of reality as integrating us with all that we can think. We can know everything in this identity. And the universe as a whole knows all things, all at once. “When mind is set free from its present conditions [of existing in time and matter] it appears as just what it is and nothing more; this alone is immortal and eternal. . . .and without it nothing thinks.”

We have to know this universal soul in order to think rationally at all.

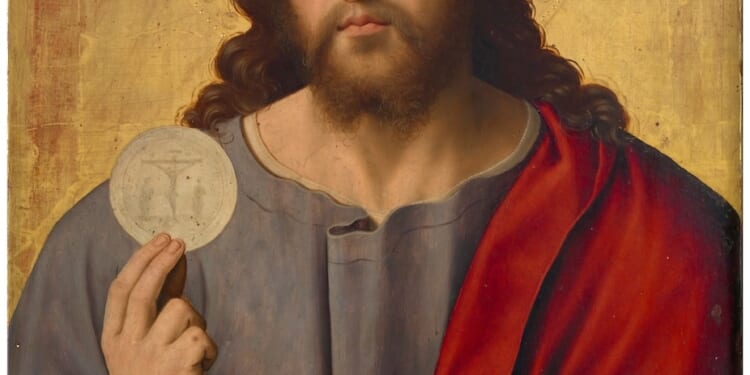

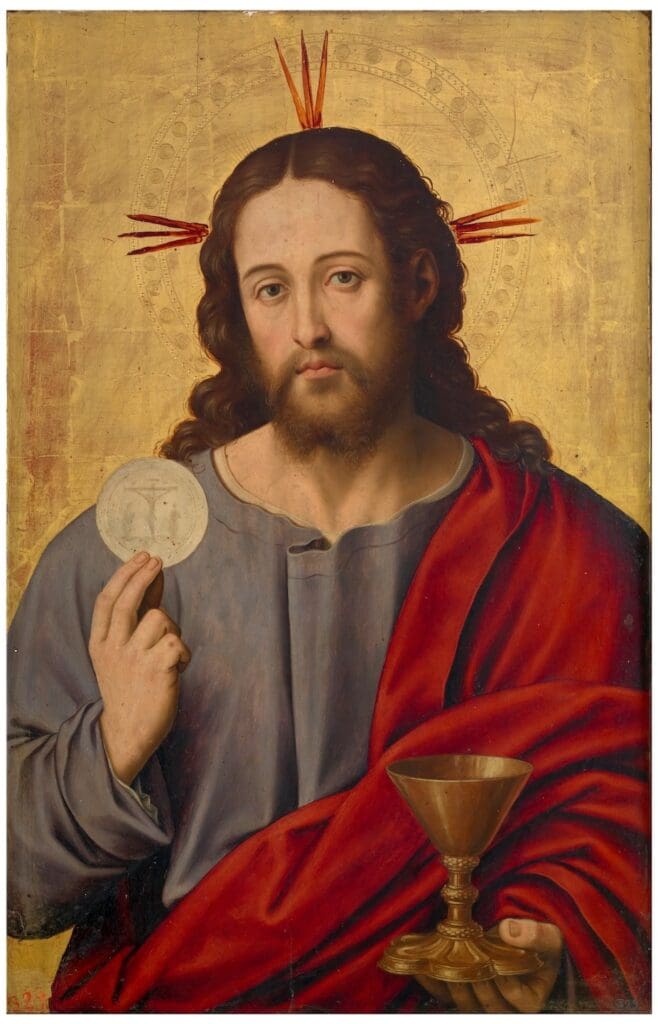

Now we can understand that Christ gives us the form and matter – His body, blood, soul, divinity – in His life and works, and in the Eucharist for us to know God and thus to know all else.

Plato and Aristotle spoke about love, but they could not know that God is love, which holds all other things together. So when Christ says at the Last Supper, “I am the way, the truth, and the life,” He answers a lot of philosophical questions and tells us what we are to know, see, love, and be one with.

He tells us what our reason should move towards. That’s real Wisdom.